Moving Identity

(adapted from my work-in-progress, The Integrated String Player)

Standing, walking, sitting, lying down, running, swimming, playing the cello, and all other activities in your life are inextricably bound with cultural, linguistic, and social dimensions. Take standing, for instance. It’s tempting to consider it a posture, an arrangement of body parts, a stack of bones, where the main thing is to figure out how to align your feet and legs with your upper body. But look at a partial list of expressions in the English language that involve standing, and you’ll see how attitude, posture, cultural mores, and other existential dimensions work together:

Stand ground, stand on ceremony, stand in awe. Stand out from the crowd, stand out like a sore thumb, stand out a mile, stand shoulder to shoulder, stand tall. Stand up and be counted.

Whenever you stand, a lot of things are possible!

Let’s conduct a thought experiment. Visualize, in your mind, a group of archetypical Argentines dancing the tango at a milonga in Buenos Aires. The music—played by the bandoneón, double bass, and piano—has a strong pull with just a hint of a marching rhythm to it. A singer expresses strong, dramatic emotions with a well-trained, nearly operatic voice. Her language, the Argentine version of Spanish, carries distant echoes of Arabic, which her ancestors spoke centuries before. The overall posture for most people in the room is very erect, the sternum a little lifted as if in defiance of convention or authority.

Now visualize a group of archetypical Brazilians dancing the samba at a bar in Rio de Janeiro. An untrained singer sings a sad-sweet song about the sunset. Her language, the Brazilian version of Portuguese, is made of soft sounds and verbal caresses. The singing is accompanied by a cavaquinho, which looks like a toy guitar, plus three or four percussion instruments of African origin. The song is mellow and swinging, and its rhythms are full of subtle syncopations and off-beats that make the downbeats a little hard to place (unless you’re born to it). The overall posture for most people in the room is relaxed; someone marks the tempo with her shoulders, someone else with her hips, a third person with her shoulders, another with her feet.

Our thought experiment involves a bit of cultural stereotyping. Not every Argentine dances the tango, and not every Brazilian is samba-crazy. Plus, there exist many styles of performing both the tango and the samba. The essence of the experiment, however, bypasses stereotyping and suggests that movement and coordination are seeped in linguistic, cultural, and environmental factors. We’ll say there exists a tango body with a tango mind, and a samba body with a samba mind. One comes with the other; there is no tango mind with a samba body. You can of course learn how to dance the tango and how to dance the samba, but for each dance you’ll need the appropriate frame of mind: a personality of movement, with its own identity.

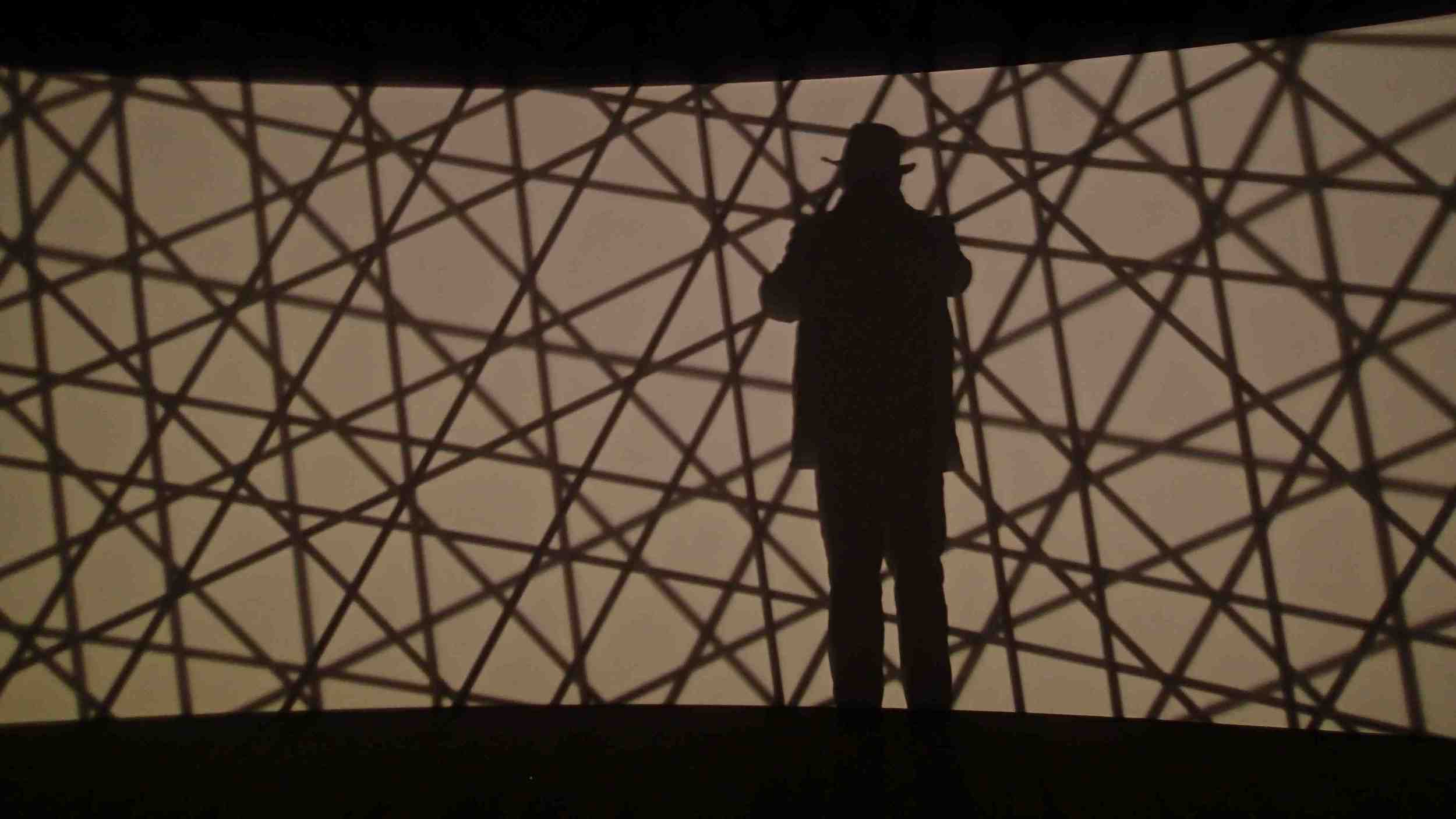

Everything you do in life has a coordinative component, which you normally think of as posture, movement, hand-to-eye coordination, position of feet, rotation of the arms, angle of head and neck, and so on. But every coordinative component is inseparable from your personality and identity. You hold the violin just so, because you are just so. Lower the violin, or raise it, and the bodily sensations and the emotions that come with them risk being foreign to you, much as the Argentine tango mind feels foreign if it tries to occupy the Brazilian samba body.

Technical challenges at the violin, then, are primarily challenges of identity. If you’re modest and retiring, you might balk at sounding too loud. But how will you play a concerto with a symphony orchestra in a big hall? You may need to become someone else, as it were. To put it more exactly, you may need to work both on your violin playing and your identity. Or let’s suppose that you’ve been struggling with back pain, and let’s suppose also that you love hyper-extending your spine when you play. Indeed, unless you hyper-extend your spine you don’t feel that you’re expressing yourself. Consciously or unconsciously, you end up preferring the problem to the solution, because the problem is “you” and the solution is “foreign to you.”

Become willing to try things that feel wrong to you: seated postures, standing postures, ways of bending your fingers, arrangements of elbow and shoulders, and so on. Be “foreign” for a moment, and see how you can cope with a new bodily identity. It might involve some play-acting, some clowning, jokes and laughter. Or it might involve a courageous psychological act that is, in fact, painful and yet necessary for your growth.

Study the art of letting go. Start with an object, for instance; let go of a knick-knack on your bookshelf and give it to a student, a friend, or a passerby. Or throw it away, period. Then let go of a habit like chewing gum. Instead of engaging in the habit, notice and acknowledge it. Catch yourself craving oral satisfaction, and decide to crave instead of satisfying your craving. The distance you get from looking at the habit, so to speak, will make the disengagement easier. Then let go of habitual verbal tics, perhaps refraining from a swear word that you tend to use too easily. The practice of letting go of little things might help you let go of weightier things: fixed ideas about posture, habits of breathing, certainties as regards your career. Let go of the hyper-extended spine, let go of the backache, let go of the song and dance of habit. Then learn a new song and dance to embody your freedom.

When it comes to identity, there are no easy changes, simple cures, or immediate results. One thing is for sure, though: understanding how physicality and identity interact is much, much more productive than assuming that you can deal with your body apart from your mind.

©Pedro de Alcantara, 2015