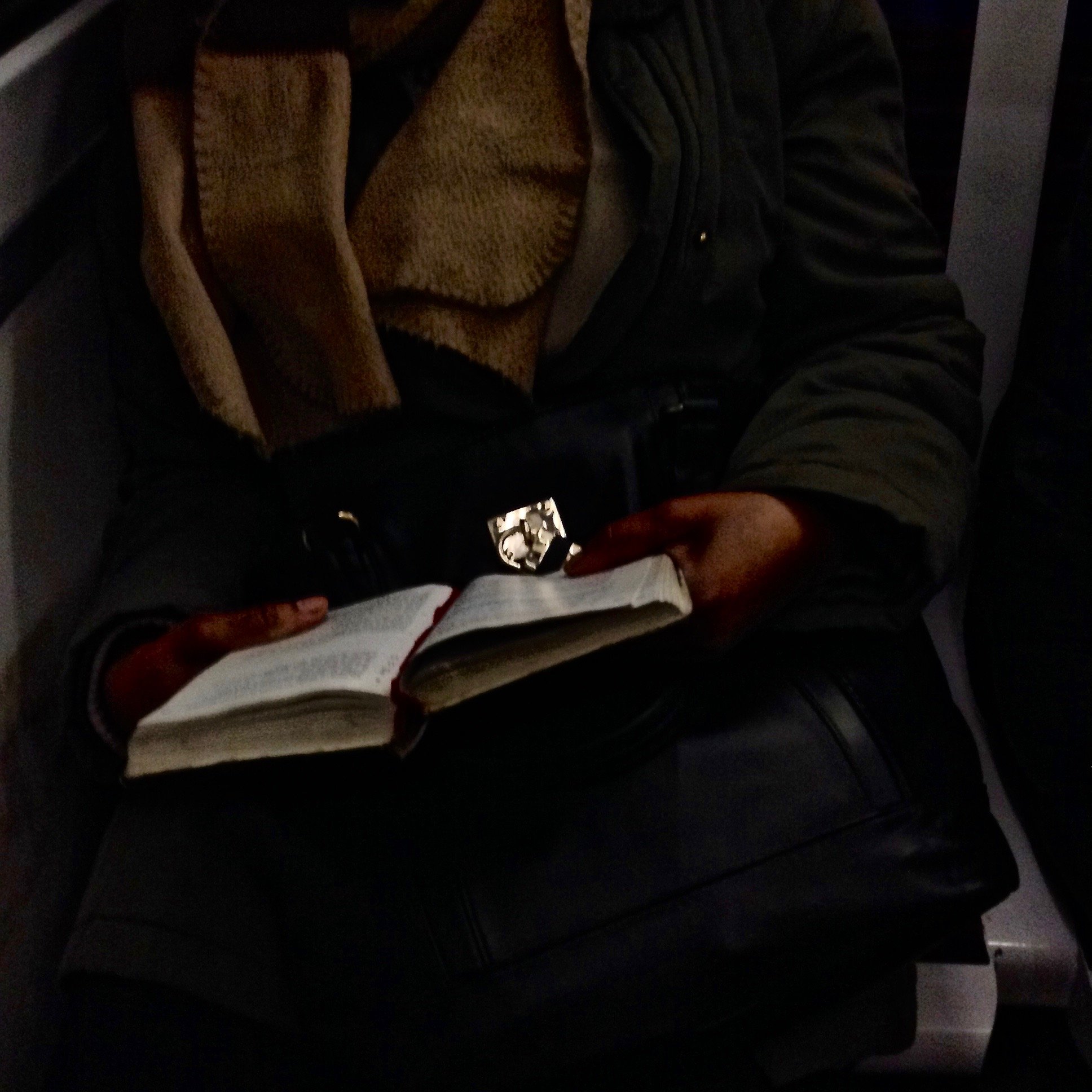

Behind a simple act there lies a wealth of possibilities. Let’s take handshakes as an example. You have shaken a thousand hands, ten thousand times. It’s a “nothing” gesture. And yet, it symbolizes connection, acknowledgement, status negotiations, agreements and compromises, thoughts and emotions. The list could go on. Yes, the list is going to go on! Palm to palm and skin to skin, physical contact, the exchange of biological and psychic energies. Shake hands with a stranger, and you’ll immediately gather a lot of information about the stranger. The information might be misleading, and you might misinterpret it, but the information is right there, under your fingertips.

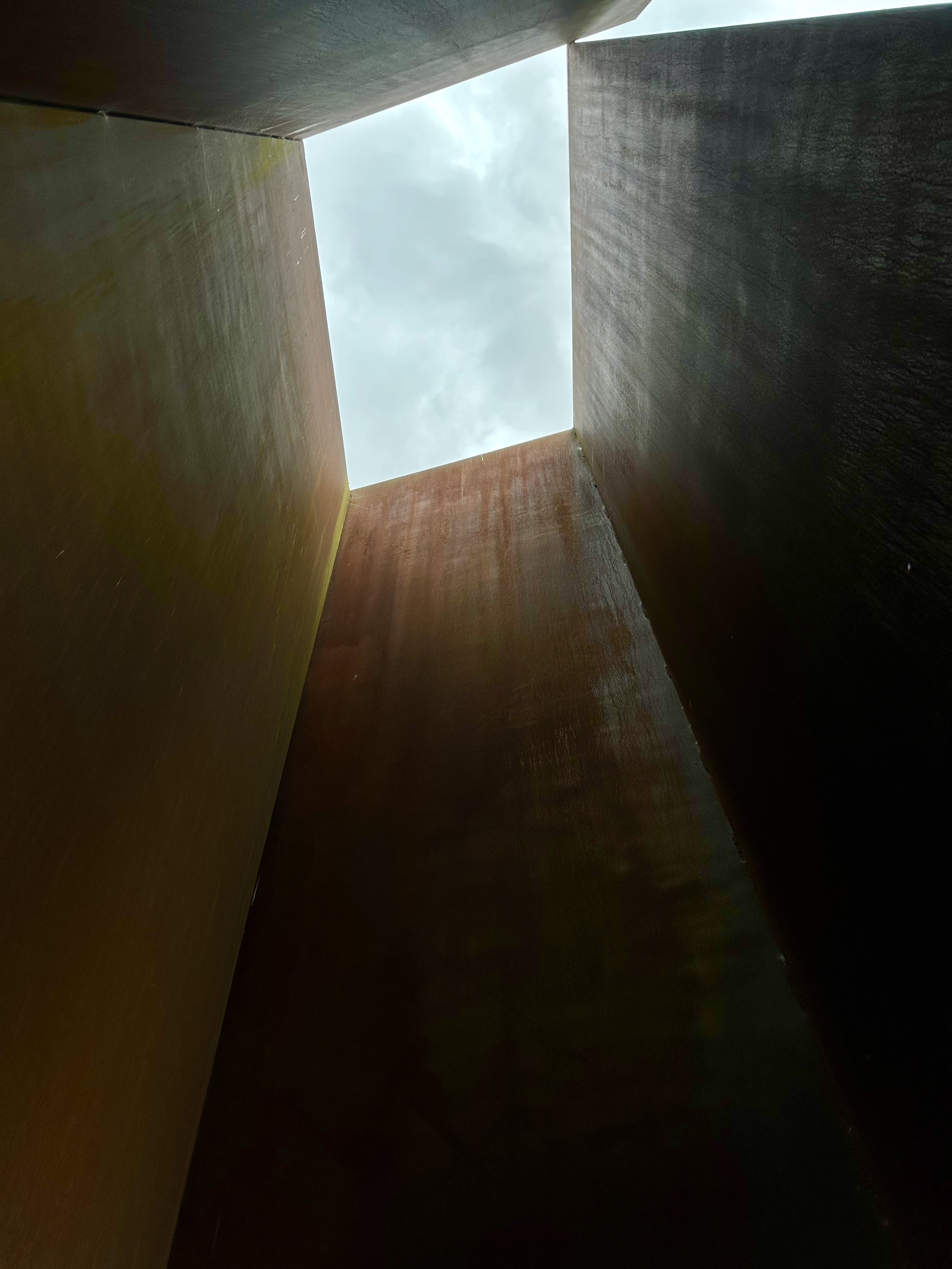

There’s the handshake, and there’s the symbolic power of the handshake. One seems banal, the other is tremendously powerful. The principle of symbolic power is ever-present in our lives. As the dogmatic types among us like saying, THE PRINCIPLE APPLIES TO EVERYTHING. Every little thing has its connections to a symbolic dimension; every little thing is a big deal waiting to come out of its cocoon.

Recently I engaged in a seemingly banal activity: buying frames for some of my drawings and putting the framed drawings up on a wall. Sure, sure, a frame; Pedro, a million people buy frames every day and put a framed photo of some kid up somewhere. Mantelpiece, kitchen counter, whatever, Pedro.

The word “frame” means a lot of different things: a picture frame, a frame of mind, an innocent person framed for a crime. A frame encloses an object, a person, an idea; that is, it closes it off from its surrounding environment and lends it an external structure, which somehow contains and constrains it. A frame separates and emphasizes something. Imagine nine drawings scotch-taped to a wall, and one framed drawing added to the group. The frame says, “I’m holding this; look at this; this one here is distinctive, it’s not like all the others.” You might frame a diploma and hang it somewhere; then the frame signals an honor or a distinction that makes you different from other people who don’t have the diploma or the training and expertise that culminate in the diploma.

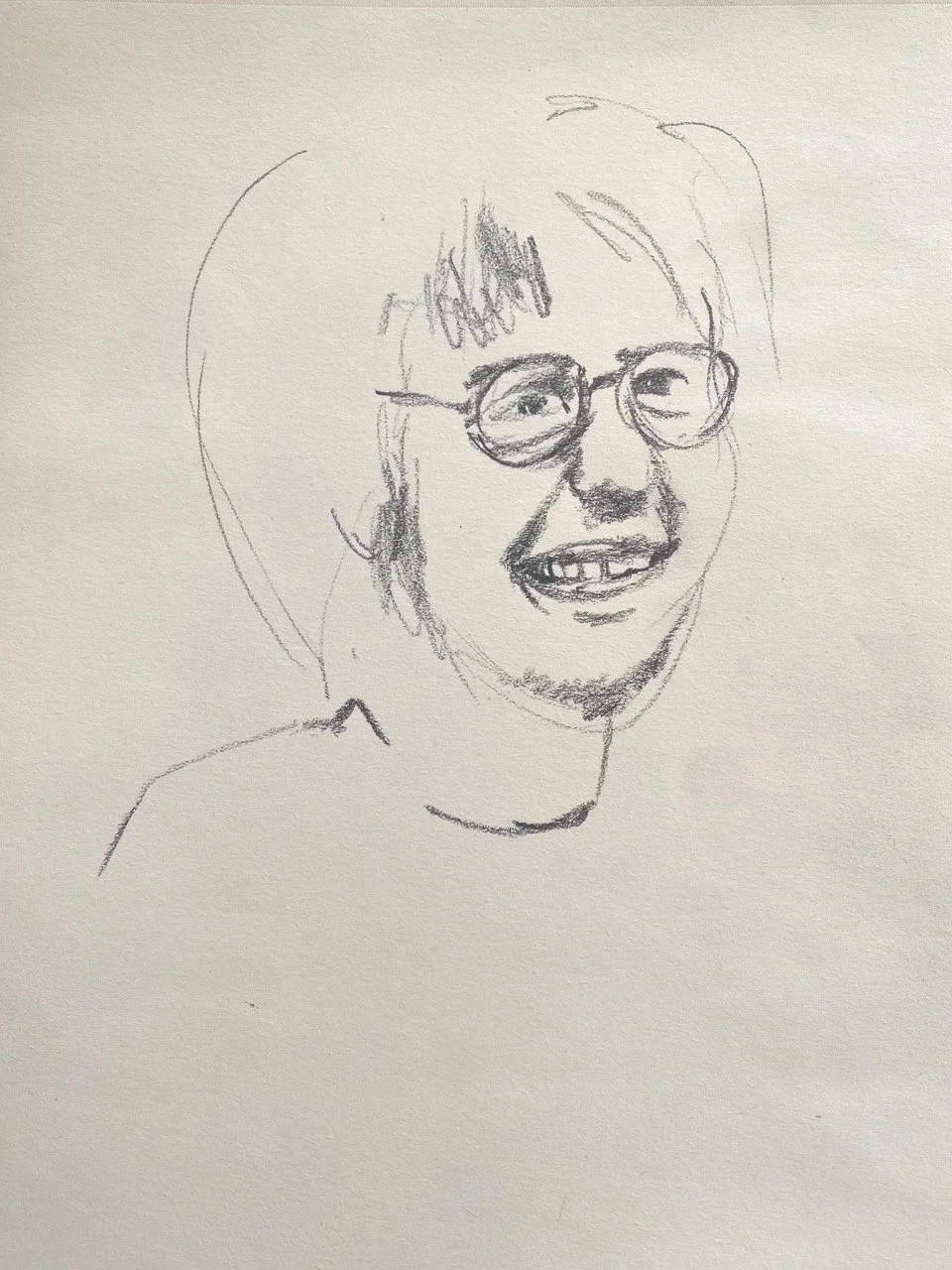

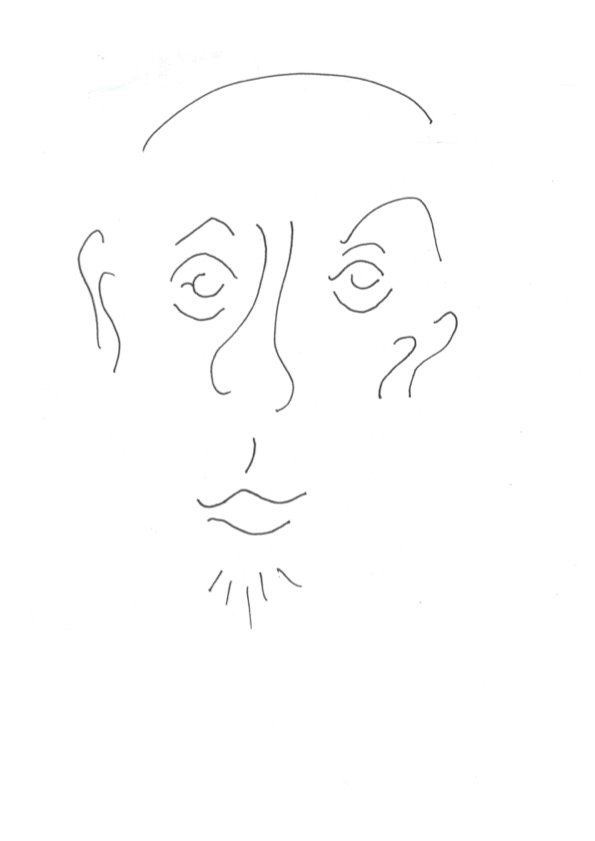

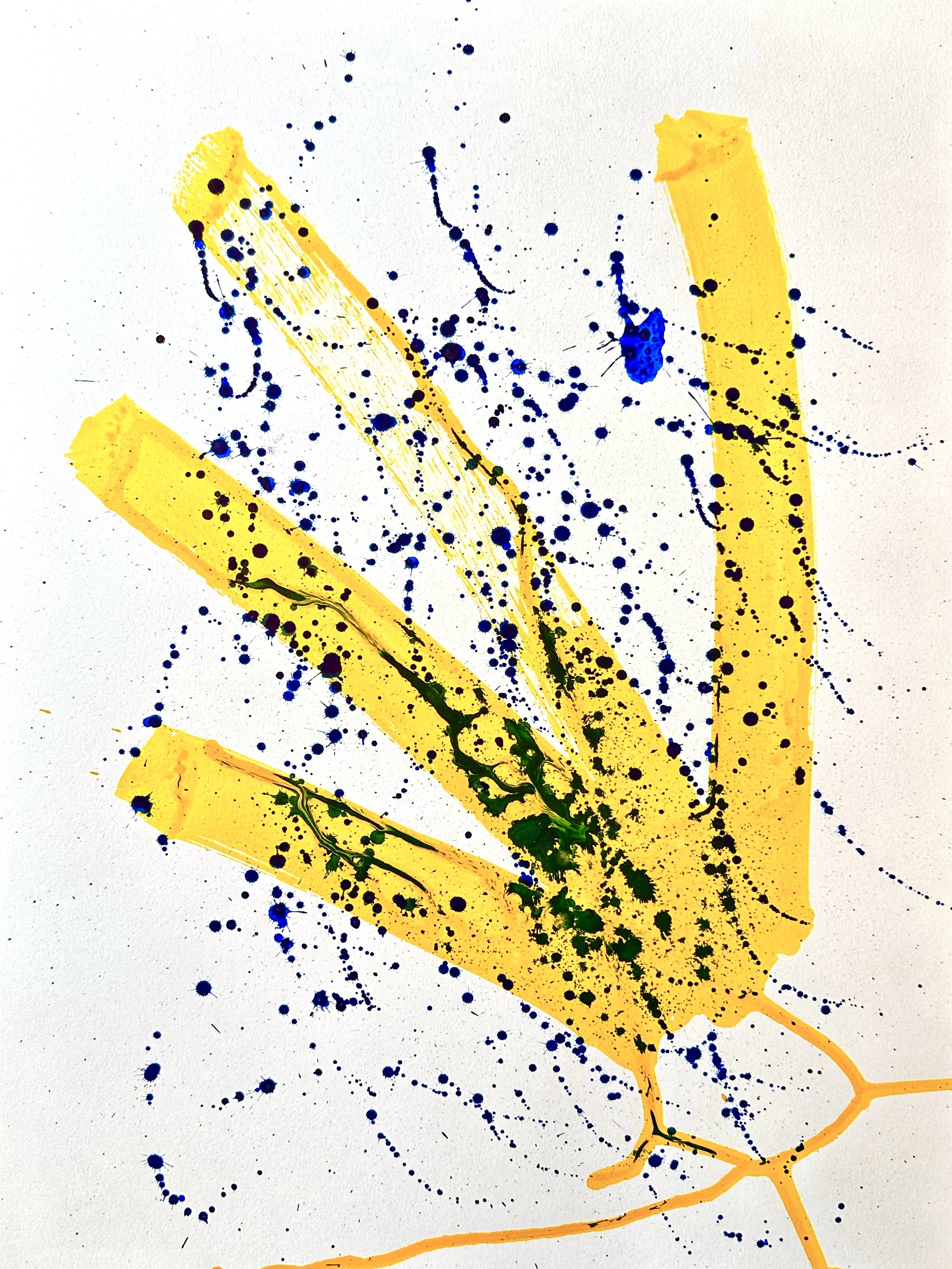

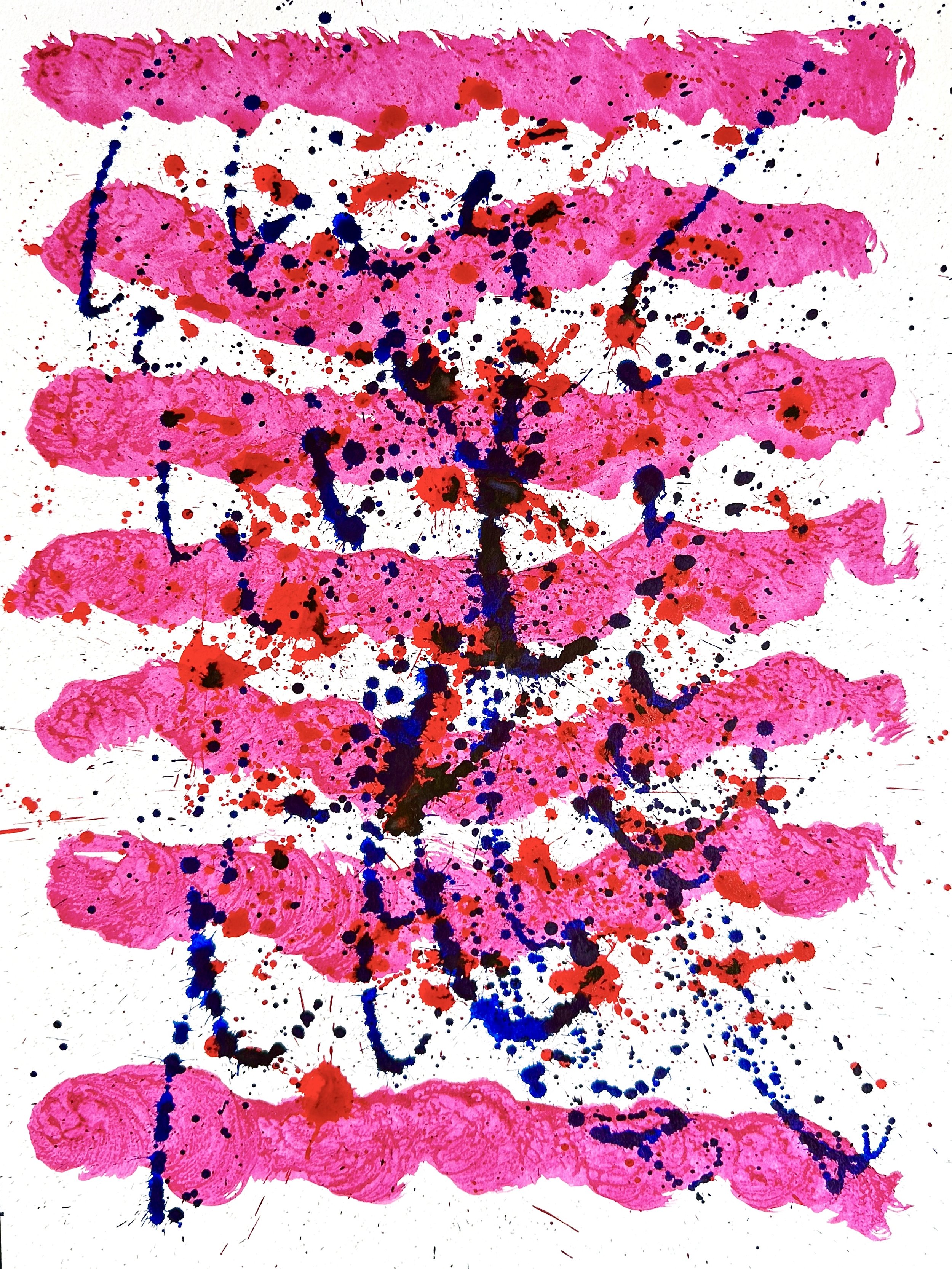

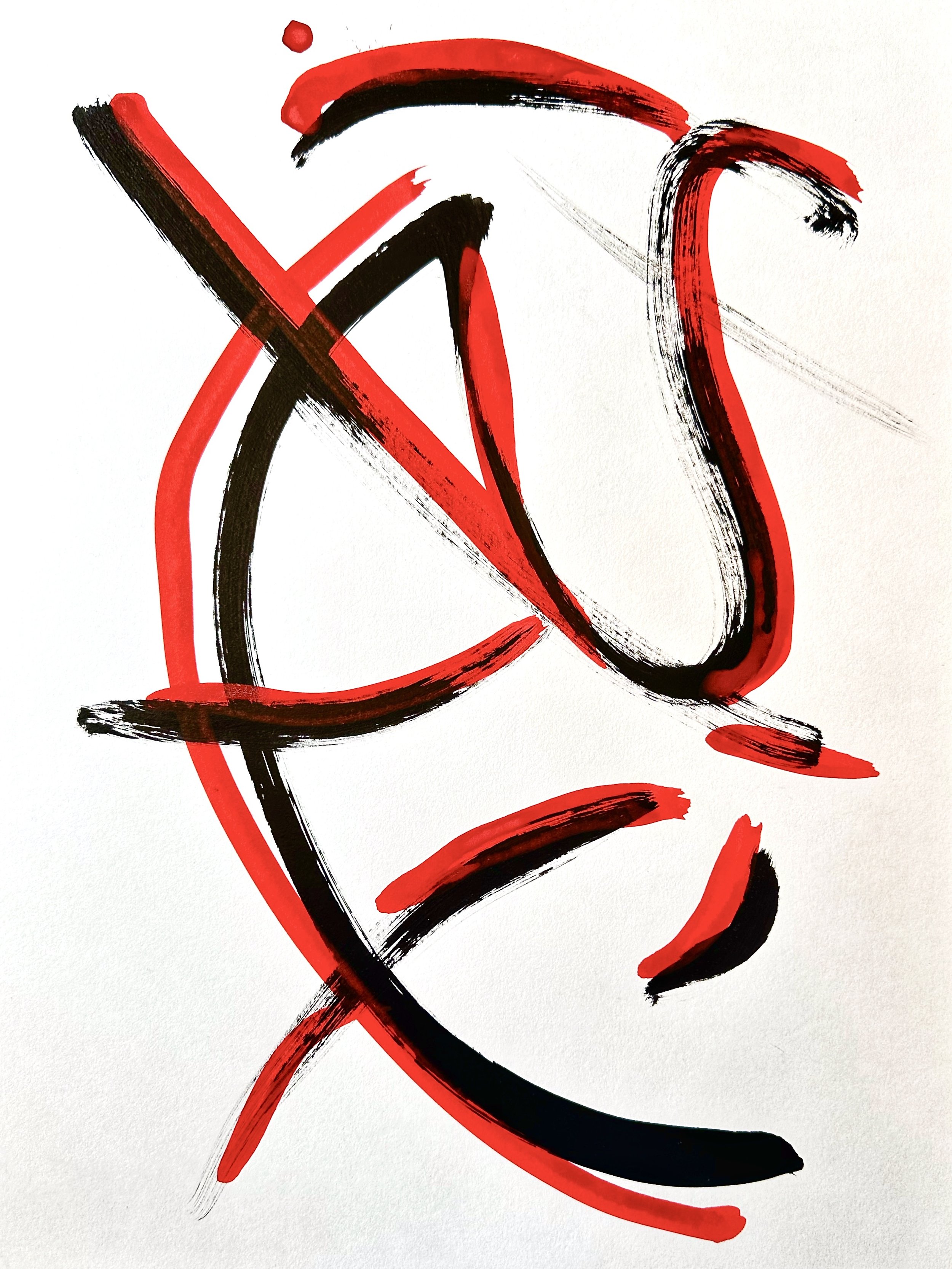

Suppose that you’ve made five hundred drawings, all of them currently inside a box inside a closet, invisible to the world. Suppose that, from the five hundred, you choose one drawing to come out of the box and to become visible to the world. Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the one in a hundred, the one in five hundred?

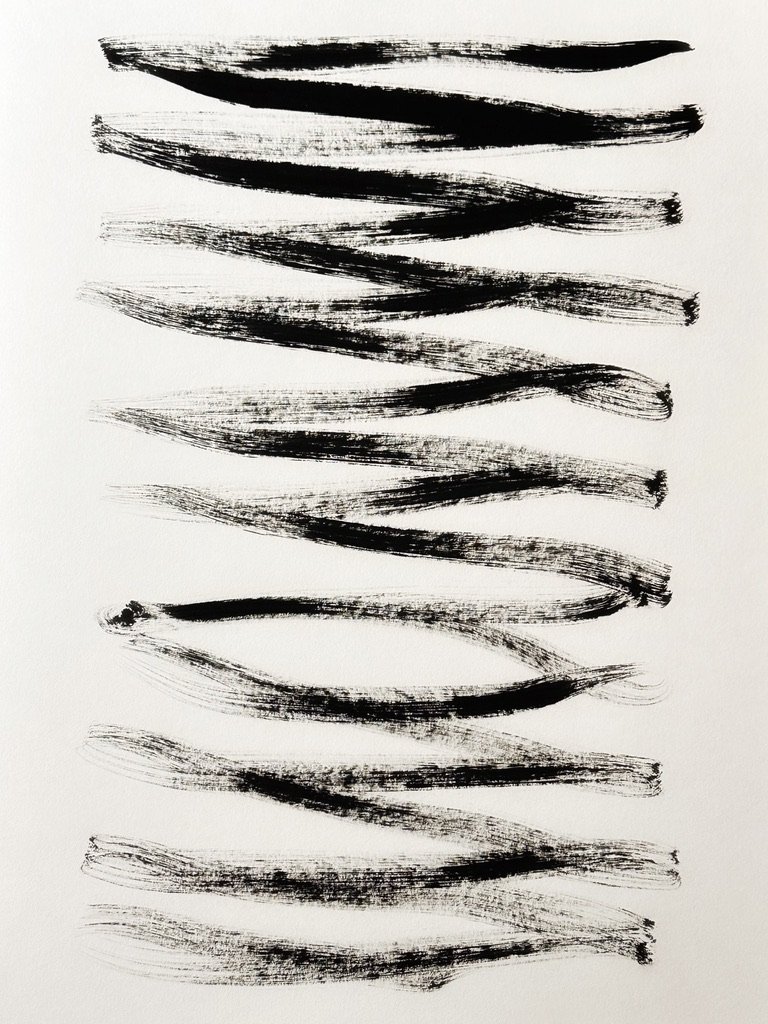

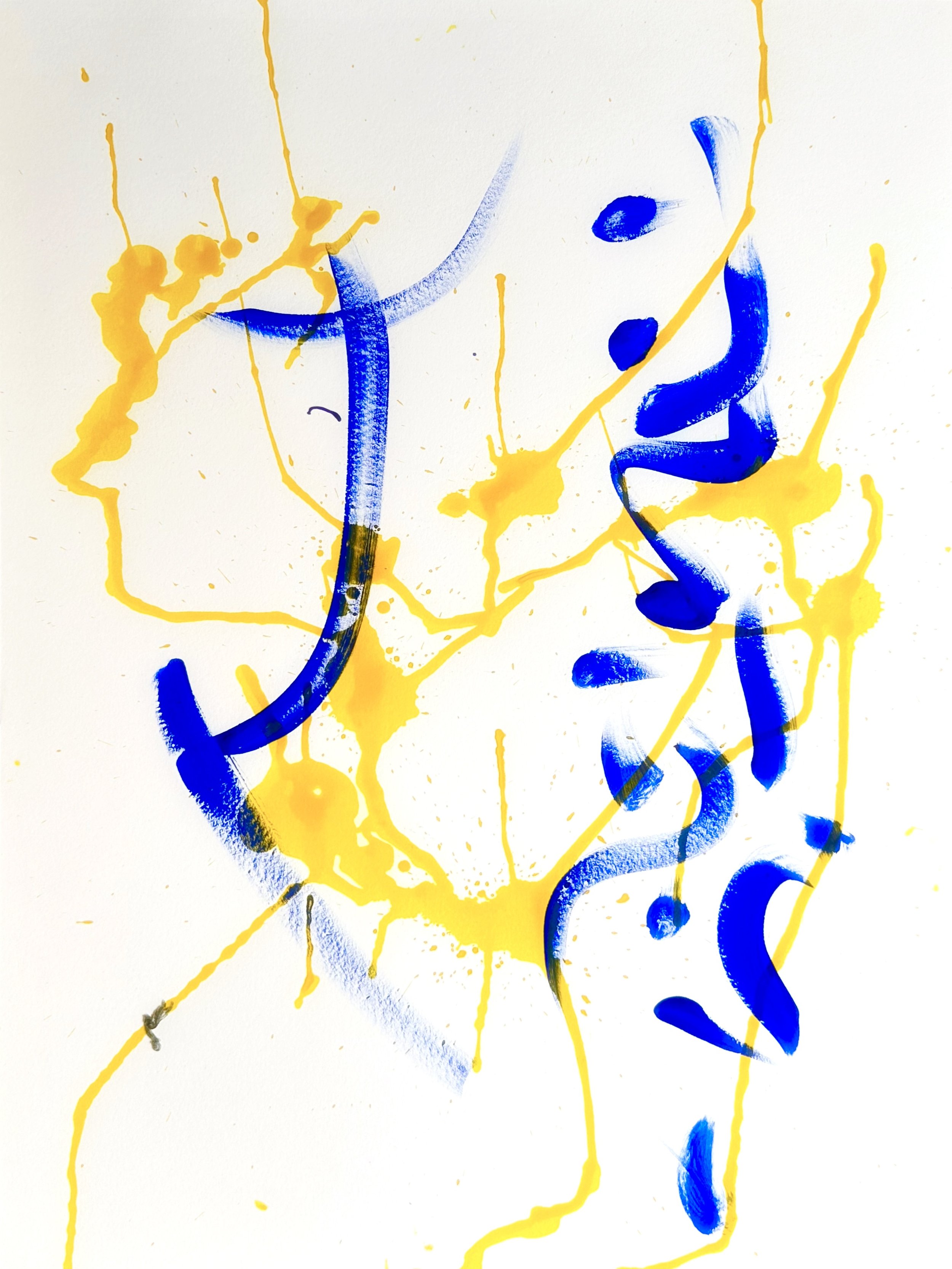

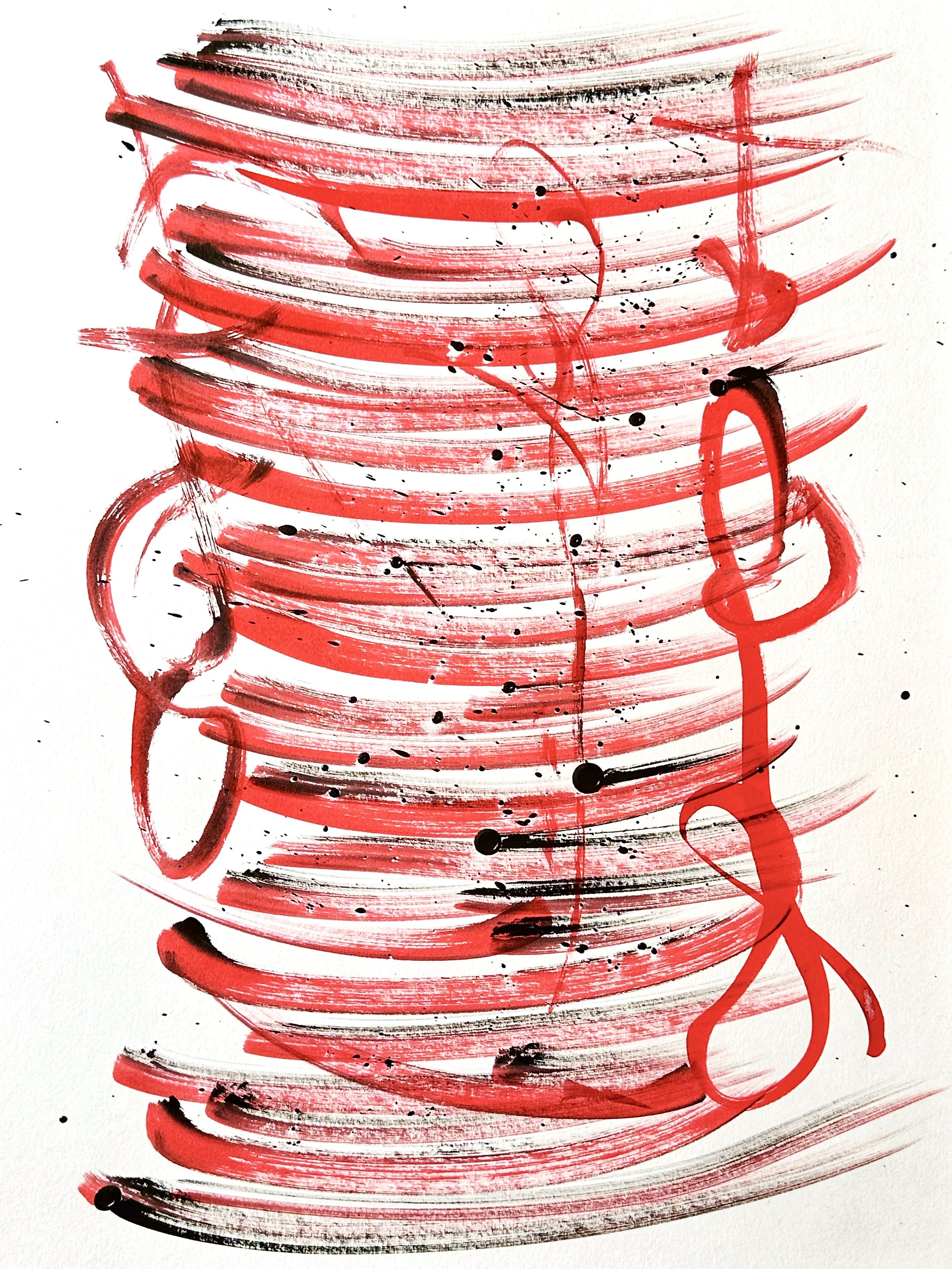

To draw is to respond to a lively creative impulse that entails movement, trial and error, transformation: the impulse becomes gesture, and the gesture becomes a sketch or image. “To draw” is an action, a verb, a process; “a drawing” is a noun, a thing, a result. Framing the object furthers objectifies what used to be a lively movement. Hey, let’s let the dogmatic artist shout his emotion: “TO FRAME A DRAWING IS TO KILL A CREATIVE IMPULSE.” Sure, sure, Pedro, you’re a murderer. We’ll visit you in jail, maybe.

My wife Alexis is a devoted builder. If we buy something from Ikea, Alexis will put it up for us while I kill some eggs in the kitchen and frame them in an omelet. Division of labor, you know? Recently I traveled to the US for two weeks, and during my absence Alexis repainted our living room with care and skill. Among other things, she painted one of our walls a color that some people would call maroon, others burgundy or garnet. We had chosen the color together; together we then chose which drawings of mine we’d put up, and in what arrangement. Together we made decisions and indecisions. (Yes, you can make indecisions, particularly when you’re framing sweet drawings for crimes they didn’t commit.) How long did it take for those drawings to go up? The procedure required an unbroken sequence of events starting with the Big Bang fourteen billion years ago. I used to be an amoeba. Growing up was rather time-consuming.

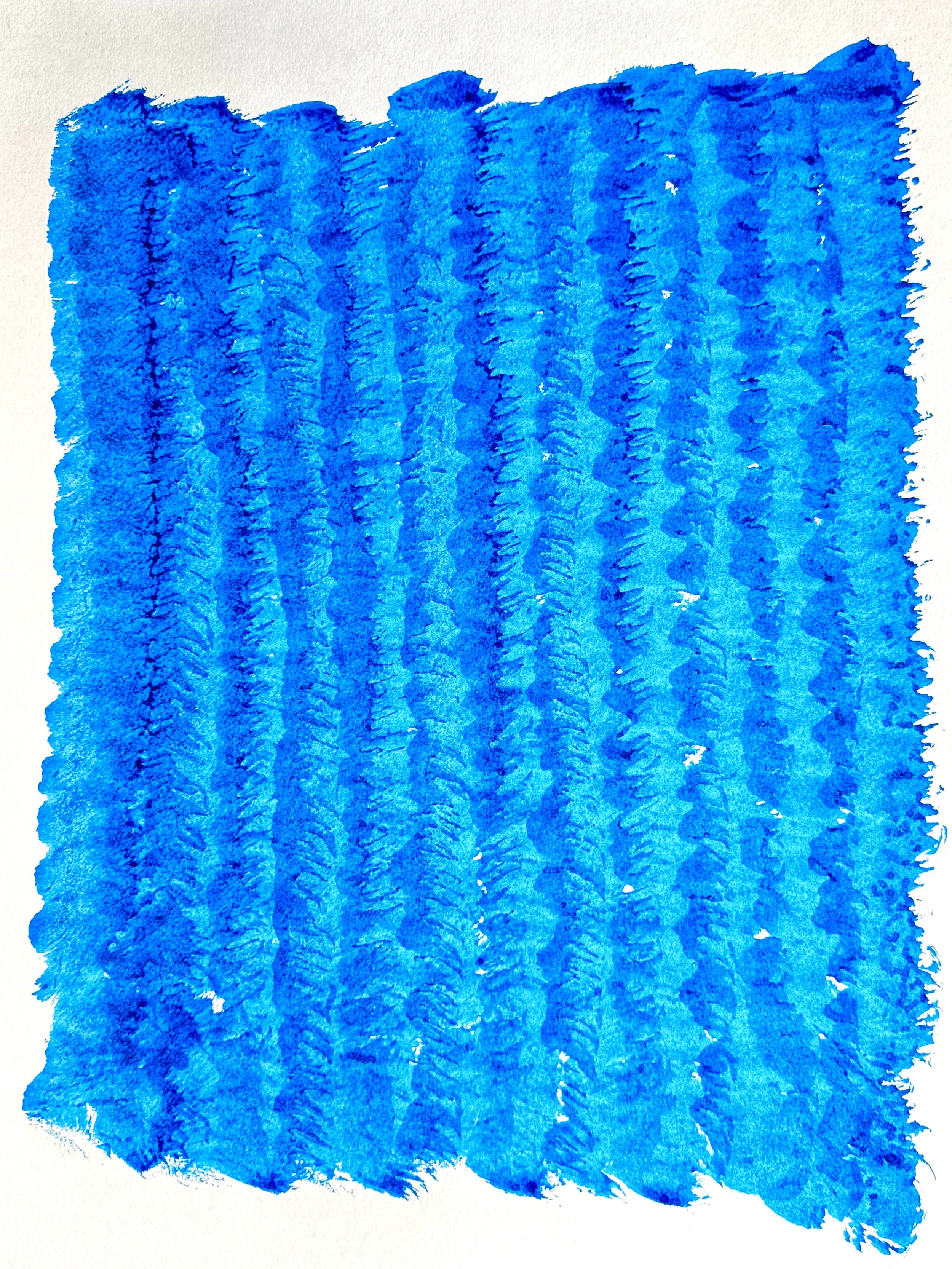

Three years ago, I started exploring brush-and-ink drawings. Some of you are familiar with the story, so I won’t tell it again. Instead, I’ll say this: the word “amoeba” comes from a very ancient root meaning “to change, to go, to move.” (Slowly.)

Wait, don’t buzz off! I want to whisper four practical takeaways into your right brain.

Many things in life are both action-and-object, verb-and-noun.

Be attentive to the inescapable symbolic dimension. It’s a big deal.

Time is bizarre. Seconds can be long, and centuries can be short.

Two amoebas met in a bar. They’re still there. If you order a beer on tap, ask the bartender to wash the glass carefully.

©2025, Pedro de Alcantara