from A SKILL FOR LIFE

THE USE OF THE SELF

Posture

Take a few moments to think about posture. What does "good posture" mean? Can you think of a few examples of people with good posture? Describe one such person in detail. Contrast, in your mind, "good posture" and "bad posture". Can you pinpoint the differences between the two? How is good posture acquired? How is it lost? What are the effects of posture, good or bad, on health and well-being?

The way you answer the preceding questions reveals much about your understanding of how human beings move, react, and live. More usefully, it gives us some pointers on both how you live yourself and how you think you should live, for your conception of "posture" entails a model of daily living.

For the sake of argument, let us imagine that you think that you have bad posture, and that you believe that classical dancers always have good posture. Now let us imagine that you think that your bad posture may be causing some health problems-backache, for instance. Further, let us imagine that you feel that your posture is bad because your back muscles are weak. If you start wishing to improve your posture, you may well be tempted to imitate the way a dancer stands or moves. You may even take dance classes or join a gym, with the express purpose of strengthening your postural muscles.

The above scenario illustrates many current attitudes about the body, posture, tension, relaxation, strength, exercise, and health. Innocuous as they may seem, these attitudes determine a practical course of action-taking dance classes, for instance, or joining a gym. If one or more of these attitudes are mistaken, however, the course of action itself risks being mistaken and perhaps even harmful.

Whether you share these attitudes or not, it will be useful for us to discuss them, for Alexander's views of the issues are in direct contradiction to assumptions which are commonly perceived as being "true". By changing or discarding certain attitudes, you would logically change or discard your course of action. Therefore, this discussion has all-important practical consequences.

One dictionary definition of posture is "the position or bearing of the body whether characteristic or assumed for a special purpose". It is a simple definition that suits our discussion admirably. Other people may define posture more narrowly, as "the position of the body".

Two problems arise when we consider posture as a bodily position. The first is that this approach does not allow for the fact that is no separation between the body and the mind, or between the "physical" and the "mental". Posture, good or bad, is simply the outwardly manifestation of a series of convictions and beliefs. In truth, posture is synonymous with attitude. This is implicitly acknowledged by language itself: we speak of somebody's political posture, or use the word to describe the attitude of a musician at his instrument. It is useful to make this connection explicit, and always think of posture and attitude interchangeably. This will help you conceive of posture as an aspect of your whole being, not relating to your body alone. Such a conception may in turn lead you to seek "good posture" in a more constructive manner than you would by simply thinking of bodily positions.

Mobility and Resistance

When you conceive of posture as a bodily position you face a second problem-it assumes that there is an opposition between position and movement. You may think, for instance, that while standing you are in a position, and while walking you are moving. The risk then arises that you will seek good posture by holding yourself in a fixed position, changing it only long enough to assume a different (but equally fixed) position-from sitting to standing, for instance. The American biologist George Coghill, a supporter of Alexander, wrote in one of Alexander's books that "the distinction between mobility and immobility is relative, and no absolute distinction can be made between them". He gave the example of deep sleep, a condition illustrative of immobility, and pointed out that, even then "the individual is mobilized in regard to its visceral, circular, and respiratory functions and the like". Unless you are physically restrained, posture and movement are just two aspects of the same state of mobility. Coghill wrote that "in posture the individual is as truly active as in movement. … One phase passes over imperceptibly into the other".

The pianist and teacher Heinrich Neuhaus wrote that "the best position of the hand on the keyboard is one which can be altered with the maximum of ease and speed". I believe that this applies usefully to all positions of the body, or to "good posture", which is not a state of fixity, but one in which mobility is either latent or realized. This does not mean that you should move incessantly. Indeed, some people move too much, in harmful ways, and often without being aware of their movements-perhaps to counteract an uncomfortable rigidity. Latent mobility means simply that you should be able to move easily and elegantly at all times, if you so wish or if the situation demands. Latent mobility also means that you may be comfortable not moving at all, even for extended periods of time-for instance, sitting listening to a lecture. Finally, latent mobility means that you may pass from rest to movement and to rest again with ease, slowly or quickly, consciously or by reflex, in innumerable ways according to need, desire, impulse, intuition, and imagination.

Mobility is not the be-all and end-all of good posture. Imagine an able basketball player in the midst of a competitive game. Even as he moves, he always retains the ability to resist other players' attempts to stop him, to unbalance him, or to push him out of the way. In effect, his mobility springs from a well of deep stability, and is in no way contradictory to it. Good posture, then, entails latent or realized mobility and latent or realized resistance.

Imagine that we are walking along together. Suddenly, you lean on me, putting your whole weight on my body, perhaps because you slipped and lost your balance momentarily. I am able to take your weight, not lose my own balance, and help you regain yours, however suddenly and heavily you lean on me. This is because I use myself well, and I am permanently ready to resist a force that acts upon my body; that is, I have latent resistance. If you lean on me, this resistance-fully operational at all times-becomes realized. I need it to push a door open, to carry a rucksack on my back or a heavy weight on my arms, to head a soccer ball into the net, and, indeed, for most activities of daily life, for work, rest, and play.

I do not need the presence of an outside force acting upon me to use my capacity to resist. Chapter 1 of A Skill for Life introduced the idea of the Primary Control-the orientation of the head in relation to the neck and back. For my spine to be as powerful and elastic as that of a seagull in flight, I direct my head forward and up, away from my back. At the same time I also direct my back backward and up, away from my head, thereby creating an opposition between the head (which goes forwards and up) and the back (which goes backwards and up). All parts of my body are in constant opposition one to the other: the head to the back, the back to the arms, the elbows to the wrists, the wrists to the fingers, and so on. This opposition gives tonus to my body, lengthens and widens my back, and increases my strength, balance, and agility. Even as I sit quietly, not doing anything, I set antagonistic pulls throughout my body-in a sense, I resist myself.

As practiced in the Alexander Technique, then, resistance, opposition, and antagonistic pulls are health-giving life forces, free from the negative connotations that these words may suggest in a different context. But keep in mind that these pulls are not the result of something that you do, but rather of something that you stop doing. For more on this, see chapter 3 of A Skill for Life, titled "Inhibition and Direction".

Use and Posture

Alexander's concept of the "use of the self" encompasses posture and goes beyond it at the same time. We know that language shapes thought as much as thought shapes language: the way you think, speak, and act shows their mutual influence. Precisely because of the dangers of thinking of posture as rigid bodily positions, it may be useful for you to think and speak not of good posture but of good use; and not of the way you use your body but of the way you use yourself.

It is possible for somebody to have bad posture (as "posture" is generally understood) but to show good use as defined by Alexander. By virtue of a birth defect or an accident, a man's back may be bent and asymmetrical. Yet, if such a man directs his energies intelligently, he will be healthier than somebody who looks straight and symmetrical (and is therefore considered to have "good posture") but who end-gains and overreacts in a given situation. (For a discussion of "end-gaining", see chapter 1 of A Skill for Life, "First Principles".) Many classical dancers appear to have good posture. Nevertheless, as you become better acquainted with the principles of the Alexander Technique, you will begin to notice that dancers do in fact use themselves quite badly, both on stage and away from it. They also have to contend with serious health problems during their careers and after retiring. If you are to abandon a rigid and narrow notion of posture, you will also need to give up seeing dancers as models of good posture. It goes without saying that there are marvellous dancers who use themselves exceptionally well; as I noted in Chapter 1, Fred Astaire was a paragon of elegance and good health into his old age.

It is possible to have good posture yet behave in an unintelligent manner. A serious Alexandrian would consider that such a person uses himself or herself badly. Here is a case in point.

Imagine a meeting, in which six or eight people are talking about politics. One of the participants sits quietly. He listens to everybody else carefully, thinks twice before saying anything, asks the meeting's chair for permission before he speaks, addresses the issue at hand without raising his voice or attacking other participants, makes his assumptions explicit, defines his terms precisely, and refers specific points to general principles. In sum, he behaves in a constructive and intelligent manner. Another participant fidgets throughout the meeting, talks to his neighbours, interrupts other speakers, raises unimportant points, speaks inarticulately, and makes personal attacks on people with whom he disagrees.

The first person may have a curved back and slumped shoulders (seen as "bad posture") while the second has square shoulders and a straight back ("good posture"), yet it is the first who is using himself well, and the second who is using himself badly. The first "inhibits and directs"-two Alexandrian concepts discussed in Chapter 3 of A Skill for Life - while the second end-gains. It is worth making the point again, that thinking, speaking, and acting together constitute the way you use yourself, which goes well beyond posture and all that "posture" means.

Intelligence

The example above may lead to another conclusion about use, posture, and intelligence. Defining intelligence is very difficulty. For a long time, intelligence was equated with academic ability, as measured by IQ tests. More recently the concept of multiple intelligences, first advocated by Howard Gardner of Harvard University, has began to earn wide acceptance. By this measure of intelligence, Beethoven, Einstein, Freud, and Isadora Duncan, to name four outstanding people, would all be regarded as very intelligent. However, each would represent a particular type of intelligence: musical, academic, interrelational, and kinaesthetic. (According to Gardner there are other types of intelligence as well as these.) A broad and multi-layered definition of intelligence is both more true to intelligence itself and more useful for the practical purposes of change, growth, and the fulfillment of human potential. For the serious Alexandrian, intelligence in its multiple manifestations is a function of the way you use yourself, and a concrete phenomenon rather than an abstract concept. You are intelligent if you live intelligently; and you live intelligently if you use yourself well, like the first participant in the hypothetical meeting described above. Incidentally, such a person is more likely to examine himself and the world around him dispassionately, therefore accepting new ideas more openly. Even if he is an inept dancer or sportsman, he would still make a better Alexander pupil than the cocky athlete who lacks a measure of composure or detachment.

The way you use yourself affects your entire emotional state. (This is discussed at length in Chapter 5 of A Skill for Life, "Emotions".) Negative emotional states-bad moods, let us call them-are notorious for their keen effects on a person's intelligence. Have you ever noticed how you do foolish things when you are in a bad mood? You may burn a piece of toast, drop a plate, cut your finger, forget your appointments, or say something you regret later. If you "do" dumb things, it is because you have temporarily "become" dumb. Logically enough, if under certain circumstances you can "become" dumb and "do" dumb things, under other circumstances you can "become" intelligent and "do" intelligent things. By using yourself well you will be, if not always in a good mood, then at least in an even one. Therefore, even if you do not become more intelligent thanks to lessons in the Alexander Technique, at least you will start doing fewer foolish things.

Tension and Relaxation

The person who thinks about body positions almost inevitably thinks of tension and relaxation too. Just as received ideas about posture may possibly harm you as you seek to improve your health, so would common conceptions of tension and relaxation.

"I am tense, I need to relax." A simple statement of a simple observation, this little phrase-readily understood by all-contains a couple of assumptions that may stand in the way of your own health and well-being. The first assumption is that tension is inherently negative; in this case, "to be tense" would always be wrong and undesirable. The second assumption is that, inversely, "to be relaxed" would always be considered a positive thing. And a third assumption follows naturally: the remedy for tension is relaxation.

Imagine a horse and its rider, a man of medium build who weighs about one hundred and sixty pounds. Despite this heavy load on its back, the horse can run long distances at fast speeds, jumping over high fences and wide ditches, and up and down a mountain.

Imagine a violin. It has four strings, attached to pegs in a peg box up on the scroll of the instrument and to the tailpiece wrapped around the violin's base. These strings bear upon the bridge of the violin with enough force to strangle a man if applied to his throat. Besides the tension of the strings themselves, the violin also receives the pressure of the violinist's bow arm. Yet the violin thrives under this enormous tension, lasting unharmed for hundreds of years.

Picture a suspension bridge over a wide river. Every day, thousands of cars, trucks, and buses cross it. At any moment there may be several thousand tons bearing upon this bridge. Yet it stands, strong and safe, year after year, without buckling or ever giving way.

The horse, the violin, and the bridge have several things in common. They are able to withstand enormous pressure. They are strong and durable. Although the rider, the violinist, and the engineer have different criteria, each would speak of the horse, the violin, and the bridge as being "healthy": a healthy animal, a healthy instrument, and a healthy construction.

Have you ever run your hand down the vertebral column of a cat or a dog? When you apply pressure upon its spine, rather than yielding to the pressure the cat will firm itself up, perhaps arching its back upwards, or perhaps just standing still and strong, purring contentedly even as you apply considerable force upon it. The feeling of a spine that is firmed is not one of relaxation, but of proper tension-the right kind of tension, in the right places, in the right amount, for the right length of time. Indeed, what gives a cat its strength, agility, power, suppleness, and speed-its overall health-is this proper tension.

The horse loves its rider. Every day as it is taken out of the stable, the horse kicks its legs up with joy in anticipation of being ridden-that is, of being made to bear great pressure on its back. If its rider were to stop riding it for a while, it would suffer as a result.

If you were to undo the tension of the violin strings and keep the instrument locked in a cupboard, untouched, for a few years, it would lose its capacity to vibrate to the touch of a bow. Musicians talk of their instruments as being "happy" or "unhappy". My own cello, for instance, "loves" humidity and is "unhappy" in dry, heated rooms in winter. A string instrument, like a cat or a horse, is happy when it is under tension, and unhappy otherwise. Like a cat and a horse, like a magnificent Stradivarius or a gleaming Steinway, like a great suspension bridge, you will be happy and healthy not when you are relaxed, but when you have within you the right tension-tension that makes you vibrate and kick your legs up in the air with joy. Once you have the right tension within you, you will be happier and healthier still when responding to stimulations that engage and heighten your inner tension-that is, you will actively seek to be tense and will avoid being wrongly relaxed.

As you read my arguments in favour of tension you may be inclined to counter that you think of cats-as well as dogs and horses and other animals-as being perfectly relaxed. You might imagine that, if we humans should draw inspiration from them, it is their marvellous capacity for relaxation that we ought to imitate.

Because a cat has the support and vitality of a strong spine, its neck, shoulders, and limbs need a minimum amount of effort to do the work they are required to do. If we could artificially weaken the spine of a cat, it would have to use its neck, shoulders, and limbs rather more actively and forcefully than it naturally does. In such a state the cat would give a fair imitation of a badly co-ordinated human being at work: awkward, inefficient, and inelegant. Relaxation, in an animal or in a human being, is a side-effect of proper tension. Conversely, too much tension is a side-effect of the absence of proper tension. The cat who seems perfectly relaxed is in fact in a state of perfectly balanced tension.

Picture a recent occasion when you felt that you were too tense, perhaps an afternoon at the office when the workload was too heavy and you felt "under stress", a long day's shopping in a crowded department store, typing at a computer, driving or riding a car, or a Sunday evening after a game of competitive soccer with friends. Perhaps even as you read this book, sitting at a café, you feel uncomfortable and distracted by a nagging pull in the back of your neck.

In any of these situations, if you think that too much tension is the cause of your discomfort, you are likely to pursue its contrary-relaxation-as an antidote. Yet, as you work, shop, play, ride, and read, you misuse and overuse certain parts of your body (your neck and shoulders, for example) to compensate for misusing and under-using other parts (the back and legs, for example). It is the absence of the right kind of tension in the right places for the right length of time that causes too much tension of the wrong kind in the wrong places for the wrong length of time, as illustrated by the weakened cat in our imaginary experiment. If, as you try to relax wrong tensions in the neck and shoulders, you further relax your spine, you are likely to create even greater wrong tensions. Badly conceived and directed, relaxation is then a problem, not a solution.

Let us recapitulate briefly. The way you use yourself encompasses posture and goes beyond it. Your posture is inseparable from your attitude; indeed, the two are synonymous. It is possible to use yourself well while giving the impression to others that you have bad posture. Inversely, it is possible to appear to have good posture and yet use yourself badly. A good position is that which you can alter with the greatest speed and ease. If you use yourself well, you pass from posture to movement and back to posture again easily, quickly, and imperceptibly. You have latent resistance and latent mobility at all times, and you activate each as needed, in turn and together. "Too much tension" is better expressed as "too much wrong tension", wrong in kind, amount, place, and time. The cause of wrong tension is the absence of right tension, and true relaxation is a side-effect of the latter. Finally, to be intelligent means to live intelligently, and to live intelligently means using yourself well.

Kissing

Kissing presents some interesting kinaesthetic challenges. A tall partner tends to stoop and reach down to the shorter one, misusing himself (or herself) in the process. Unwittingly, the shorter partner aggravates the problem by making herself (or himself) shorter still.

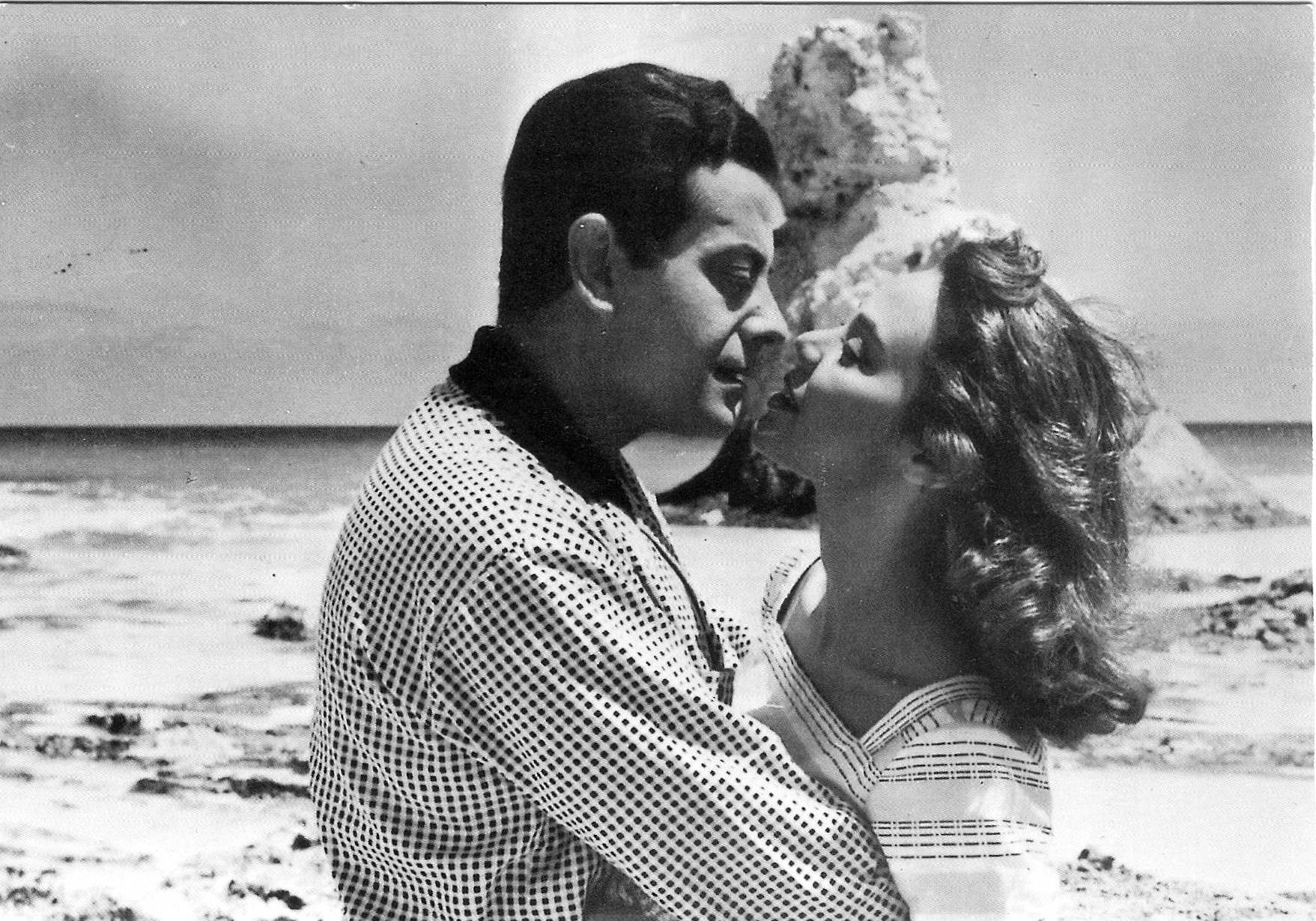

Look at how the Egyptian actress Maryam Fakhr ed Dine, in a scene from Risalat Gharam (left photo), takes her head back and down as she gazes into the eyes of Kamal al Chinnawi. She contracts her head into her neck and rounds her back and shoulders. For a man to kiss a woman whose neck and spine lack tone is startling, even unpleasant, like trying to play a violin with a loosened bow.

Madga, another Egyptian actress, uses herself in a wholly different manner (right photo). She lengthens her neck, which becomes a natural extension of her spine, and makes herself taller - and more enticing - even as she tips her head backwards. This makes the act of kissing Farid al Atrache (in a scene from Min Agl Hobbi) kinaesthetically easier, and, one imagines readily, more satisfying for both partners.