The other day I decided to go spend some time at the Gare de Lyon, a major train station in central Paris. If you’re traveling down south, to Lyon and Marseille and Switzerland and Italy, it’s here that you’ll board your train. And it’s here too that you arrive in Paris if you’re coming from those other marvelous cities and countries.

Over the decades that I’ve lived in Paris, I’ve been to the Gare the Lyon hundreds of times. But there’s a big difference between going somewhere with the goal of doing something, and going somewhere with the goal of being there. To linger, to see, to explore; to photograph and to record; to talk to people . . . it’s very different from taking a train to go on a dutiful business trip.

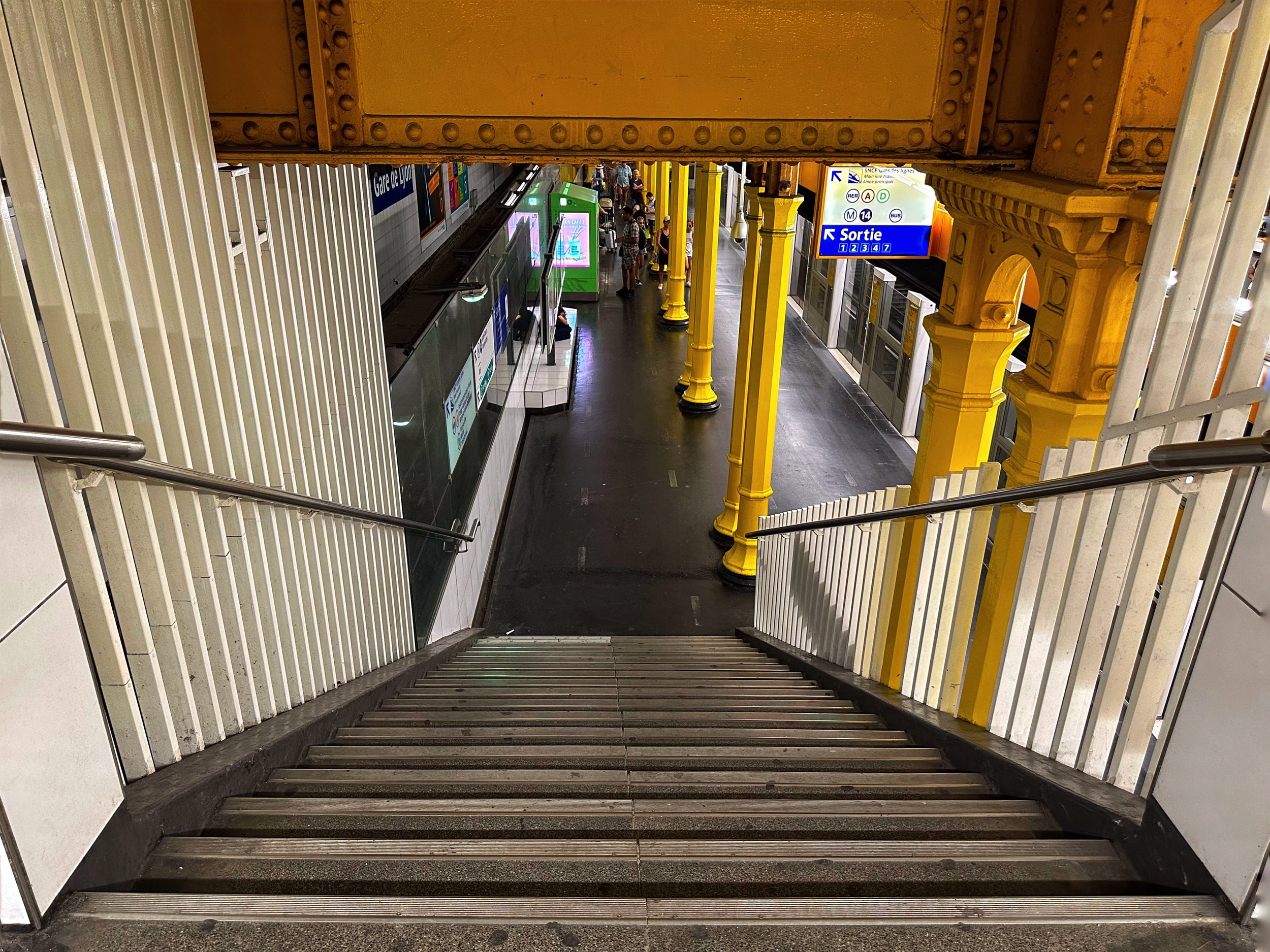

This map gives you a notion of the station’s size and its many entrances and exits. There are three halls where trains arrive and depart; two of the halls are contiguous. Underground, there are two metro lines and two suburban express lines, their tracks far enough from one another that it might take you ten minutes to walk from the express track to the local one—or from the metro to your train track. Imagine this is your first visit to the station; you don’t speak French, you’re a little late for your train, the day is hot and the station is crowded. To navigate the Gare the Lyon isn’t easy. People miss their trains, people get lost, people have emotions.

Now imagine that you’re at the station not because you have to, but because you want to. You’re not late catching a train; time is suspended, especially for you. 30 minutes, three hours; you stay for as short or as long as you wish. It’s like visiting a museum, a beach, a city square, a monument: exploration for the love of exploration, for the love of architecture, art, and history, for the love of seeing things and watching people and interacting with the world.

A few years ago I did the same thing at the Châtelet-Les Halles metro station, and I blogged about it here. You don’t have to be in Paris or in a beautiful city to undertake the exploration. Recently a group of my students and I explored an underground parking garage with three levels—a well-built, clean, safe, cinematic space. We slowly descended level by level, we stood in corners and along walls and passages, we sang drones and songs to amazing acoustics, we watched cars drive by with funny-looking families looking funny at us. I don’t know how long the exploration lasted; maybe 45 minutes, maybe one hour. Then we “came out into the open” through a discreet door that led directly to the sidewalk outside, and the perceptual shock of fresh air and city bustle was awesome.

At the Gare de Lyon, a singer-songwriter was performing in one of the corridors. The public-transport system auditions buskers every year. There are designated spots for musicians in stations, corridors, and hallways. Kuku is an American of Yoruban-Nigerian origin. I watched him talk with great care and patience to a woman—a passerby—who wanted his attention. Afterward I too wanted his attention, and he talked to me with great care and patience. Then he performed and I recorded him. His life-affirming music resonated left and right.

An attractive young man with a pleasant disposition was sitting at a store selling phone accessories. We chatted, and I asked him if I could take his photo. The idea tickled him. Another pleasant your man, working for the metro, was happy to be photographed but wasn’t sure his bosses would agree to it. He hammed and hawed very sweetly, and then I told him I’d “take his photo against his wishes” and he could tell the bosses that there was nothing he could have done about it. He smiled and “I shot him.” A traveler trying to find out where his train would leave from approached me for assistance. He had a lovely hat on, and a kind, relaxed demeanor. He let me take his portrait, and we parted ways not knowing each other’s names. There were four security guards in one of the halls, two men and two women. The women didn’t want to be photographed, no way! The men agreed readily, and it felt to me that one of the guys was trying to prove to the girls that he was tough and fearless! Let the strange stranger photograph me, what do I care!

If you don’t know the station and if you’re distracted by crowds and announcements, you might not see that there’s an incredible restaurant up on the second floor. Le Train Bleu was built at the same time as the Grand Palais, the Petit Palais, and the bridge Alexandre III, all of it related to the universal exposition of 1900. The architectural style of the restaurant has been called “neo-Baroque Belle Époque.” There is a warren of spaces beyond the restaurant proper where you can sit and relax with a coffee, or have meetings with other important people like you. Is the coffee expensive or cheap? It depends on how you pay attention to the setting, the people, the history of the place. The more attention you pay, the cheaper the coffee gets.

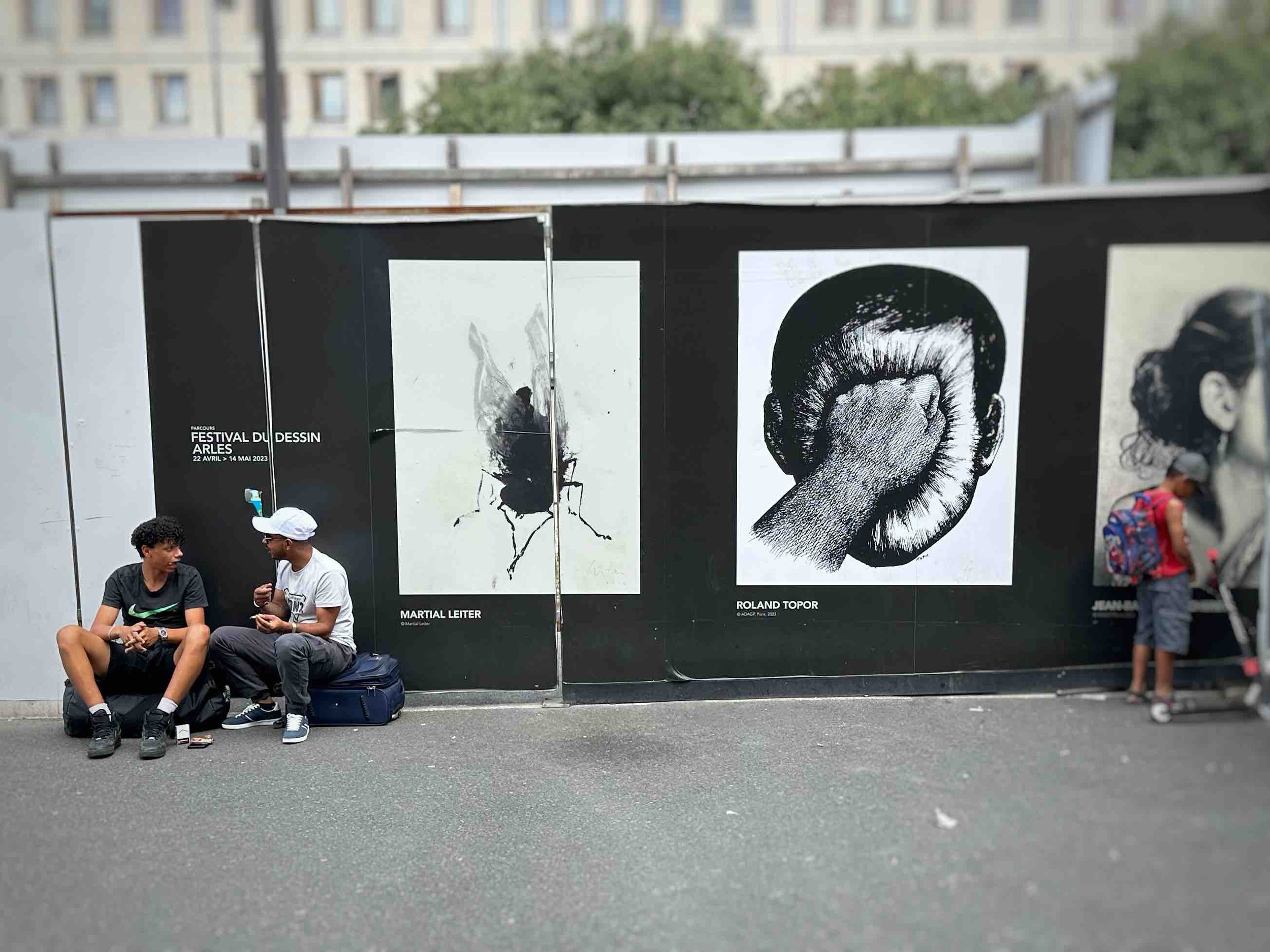

The esplanade in front of the main entrance to the station always has art, photographs, and suchlike in big panels displayed in rows. On this visit there were, among other things, reproductions of drawings from a show that took place in Arles last spring. You can’t see the art without seeing the people sitting against the art, chatting and smoking; or the boy peeing against the art; or the idle passersby waiting for Godot.

I was at the station for two hours, and not for a second did I feel bored. The station, “like the world,” merits repeated visits.

©2023, Pedro de Alcantara