The creative process is a totality. Some people might call it a whole world. Pretentious intellectuals like me like calling it a Gestalt, which is the same as a totality but the word has nice echoes, connotations, imaginings. You can take the Autobahn from Gestalt to Bauhaus.

When the totality doesn’t completely envelop your creative efforts, you’re likely to come up with crappy results. If, however, you dwell in the totality, results are, in themselves, secondary—and likely to be quite satisfying.

A young child digging a hole in a sandbox is immersed in the totality, and for this reason we find the child terribly lovable, worthy of veneration. The hole is secondary, but fascinating were you to analyze it. But let’s leave the hole aside and notice the totality. There’s the environment (a sandbox in a city park, late afternoon in summer); the materials of the creative work (bucket, scoop, sand); the commitment and investment of the young child in pursuing a goal (digging, digging, digging a hole); the psychomotor presence of the child, barefoot and in a deep squat (the animal living in space and time); the paradoxical mixture of “I’m just playing” and “This is serious business” (serious business); the silent stories that the child is telling herself and has been telling herself ever since she told herself her First Story (Indiana Jones); and the elemental, symbolic nature of the act (sand, sandbox, beach, desert, caravan, thirst, mirage, oasis, infinity, eternity). All of it is happening at the same time: it’s not a linear sequence (this, then that), but a kaleidoscopic amalgamation of all dimensions into a Gestalt (Autobahn).

It doesn’t matter in what domain you pursue the creative process: visual arts, music, writing, cooking, architecture, professional therapeutic work, politics, mathematics, brain surgery, TikTok. In the totality you shall find meaning, direction, and practical results. Not in the totality? Your brain-surgery patient will be “accidentally” lobotomized. By you, of course.

I recently added a domain to my creative pursuit: drawing with brush and ink. It’s a natural development within my drawing explorations, but it’s a new thing for me. If ever I did anything with brush and ink, it might have happened in seventh grade but I have no memory of it whatsoever. Therefore, it never happened! Ever, whatsoever, never!

It’s a new thing, I’m telling you.

There’s an art-supply store about five or seven minutes’ walk from my home. It’s packed, packed! with everything, everything! that I might want or need for an art project, art project! Sometimes I go there to buy nothing but a pencil—just to go there and to soak in its atmosphere and to dream of colors and shapes. I went in and chose an A2 sketchbook, on sale at 5 euros which is 5 dollars. 25 sheets of white paper, each sheet already an art work, practically by birth. A2 is the equivalent of four sheets of office paper: smaller than the Himalayas, but larger than a ladybug. I needed a brush. I have no experience with brushes, with using them, or with buying them. What kind, how big, how small, how expensive? I don’t know! The store has hundreds of brushes to choose from! Which one? I don’t, I don’t, I don’t know know know! And I picked one, medium sized, inexpensive: ultimately, it doesn’t matter which brush I get, because I’m just entering the maze and any portal will do. The main thing is to pass through and go in. Overthinking your choices can be nicht-Gestalt, so to speak.

I approached the manager to ask her about ink. French friendliness is different from American or Brazilian friendliness. The manager is somewhat serious, like a schoolteacher about to give you a grade lower than you expect. But I think it’s a façade: I bet she’s the archetypical schoolteacher who really cares for the kids in class, but who doesn’t externalize her caring because she risks crying with too much love. She’s direct and clear, businesslike. Showing her my brush, I said to her, “I don’t know what I want, I don’t know if you have it, and I don’t know where it’d be if you have it.” I mimicked sticking the brush into an invisible pot of ink, stirred it, and provided a slurpy splashy soundtrack. She understood me to perfection. She walked me to the corner of the store where the inks hid in plain sight, and she suggested an inexpensive pot of black ink appropriate for my learnings. I asked her, “Do I have the right to adore you?” She laughed briefly, then said, “Sure, I like it when people adore me.” I paid and left. Paper, brush, ink, and the help of a benevolent goddess in finding it all. Plus, a story that is meaningful to me and that will be forever associated with my brush-and-ink explorations.

Materials, discovery, pleasure, adoration. Territory, exploration, orientation, pleasure, joy. Adoration. Repeat yourself deliriously when you’re having a spiritual breakthrough: pleasure, joy, adoration.

Did you know that ink has a staining property? Blotch, splotch, fleck, speck, early death, crematorium. There’s no way I could blotch my wife, I mean, my home, my golden carpet, my babies, my cats, my cello, my piano, my heirlooms, or my wedding dress (some items on this list are fictional). I decided to go draw in my courtyard downstairs. I put on a pair of gym shorts and an old T-shirt, and barefoot to the courtyard I went.

My courtyard is a rectangle of perhaps 60 square meters. Low-slung apartment buildings on every side. Windows looking in. Four small olive trees in clay pots, though not producing olives. Two water taps, one of them with a hose attached, yes! And six or seven garbage cans in the standardized French format (here they’re called poubelles, and we use them for general waste but also for recycling paper and glass). I’ve lived in this building for 20 years, and I’ve entered and exited the courtyard thousands and thousands of times, each passage imprinting a little something in my memory, physical and emotional. I played concerts here during the pandemic confinement: short performances of my own music, for an audience of a few neighbors including two wonderful little kids.

I put two of the cleaner recycling garbage cans side by side and covered them with an old bedsheet. And this became a stable surface on which I could lay my sketchbook.

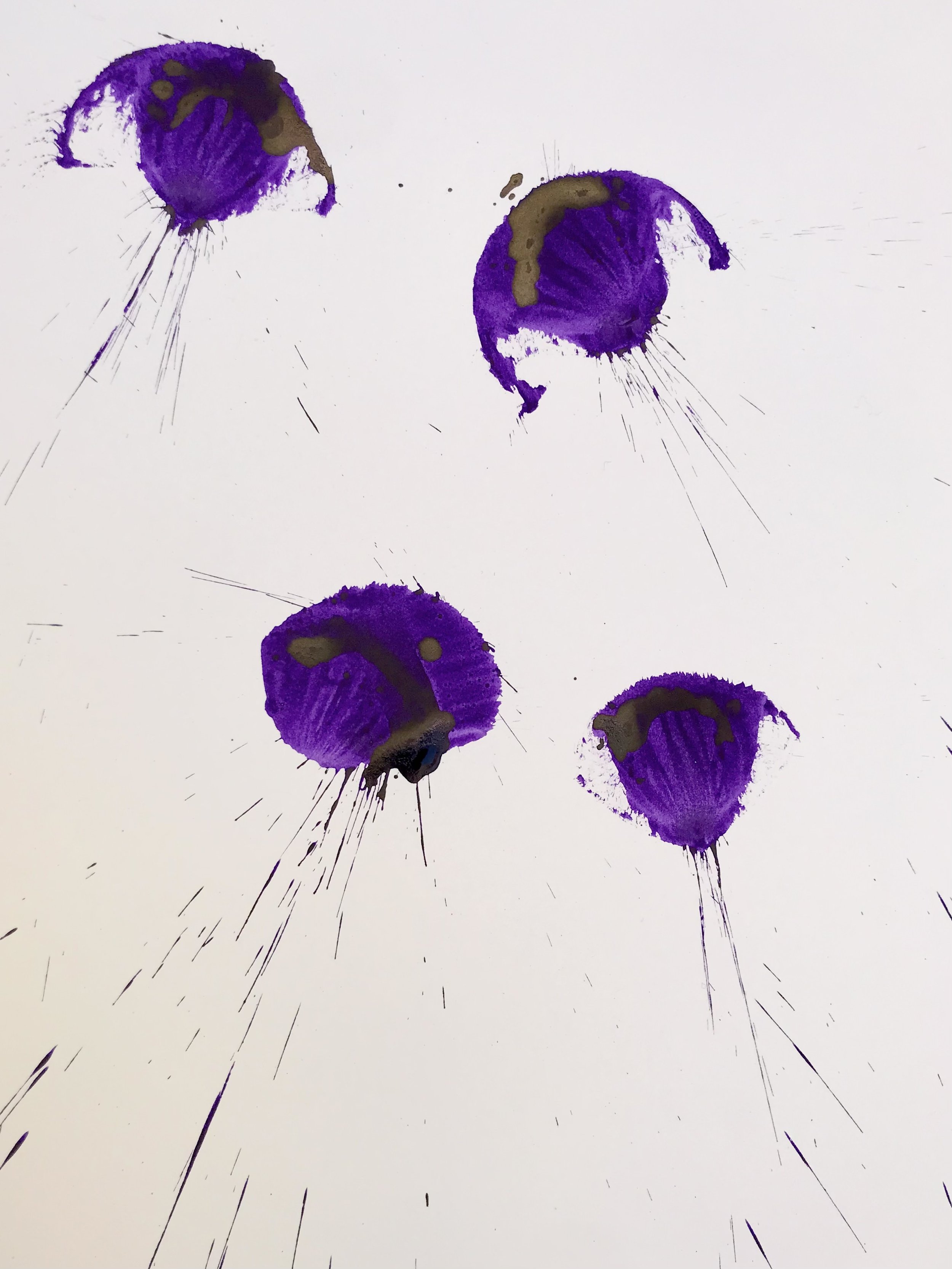

Neighbors come and go. There’s a subtle soundscape, mostly faint and distant: airplanes, city traffic, doors opening and closing, roadworks. The soundscape is caressing and agreeable: the city is alive, the buildings are alive, the neighbors are alive. Once I knew everything and everyone was alive, I started the physical, oh the very physical process of splotching and splecking. Brush into ink pot, brush onto page, gesture, movement: this is a drawing, this is art. It’s a dance, it’s Tai Chi, it’s air guitar, it’s shadow boxing, it’s squatting like a little child digging a hole. After I draw, I pull the page off the sketchbook and I lay it on the ground to dry. A work session might encompass 25 drawings, 25 dances.

Art is life is paradox. Nobody can define art, and nobody can encapsulate life. How hard am I thinking when I splotch a sheet of paper? It’s paradoxical, because my goal is and isn’t and isn’t and is to make art. My goal is discovery and pleasure. My goal is joy and adoration. My goal is to be barefoot in summer. My goal is to move as if not thinking, and yet my accumulated thoughts of 64 years are inevitably present when I move as if not thinking. I make gestural decisions. I test angles of contact. There’s speed, rhythm, and choreography. I’m clear and vague, I’m determined and flexible, I know a lot and I know very little: it’s all true. To the casual observer, it only takes me three seconds to do any one of my drawings. But that’s misleading. Each drawing takes me 64 years and three seconds.

The creative process is like a swimming pool or a pond or the ocean. I’m inside it; I’m enveloped by it, bathed by it. I float and I swim. The current takes me somewhere, and I follow along. Or, like a dolphin at play, I take the initiative and I jump out of the water and fall back into it again. The main thing, though, is to be in the water, totally; and not separate from it.

Last year I went to hear a famous violinist give a performance of classical music at one of the main Paris concert halls. Once he started playing, I quickly knew that I’d sit there waiting for the first half of the concert to be over, passing the time in frustration and resentment until I could rush back home during the intermission. The fellow wasn’t immersed in the totality; his playing was smooth and very, very professional. But . . . no. He wasn’t “total,” and the experience of watching him wasn’t “total-inducing.” Mine is a subjective perception, needlessly harsh, difficult to explain and to justify. Next time we meet, you and I will share subjective perceptions and harsh judgments, and we’ll do our best to justify them. Or maybe not. Justification is overrated.

We go to the movies and become irritated at something with high production values but no immersion in the creative totality. We start reading a book and sometimes we want to throw it out of the window, or we wish harm upon the writer, famous and accomplished as he and she may be. A painting can sell for millions of dollars and yet be creatively worthless. A gleaming new building goes up in a nice neighborhood, and we take one look at it and we see catastrophic waste, an urban-planning disaster, a moral failure. And we do our best not to dynamite the building.

Territory, materials, motivation, joy, pleasure, stories, paradoxes, symbols, metaphors. Adoration.

The other day I heard someone say, “Art is all about expression.” I didn’t dynamite the building, but I strongly disagreed! Mentally, in silence! “Art is all about connection,” I blasted telepathically.

“Oh, yeah? Connection to what?”

“Let’s go to the Place des Vosges. A little kid is digging a hole there.”

©2022, Pedro de Alcantara