Many people tend to define creativity in artistic terms—having to do with painting, music, and literature, for instance. And many people think that creativity has “techniques and standards.” On this account, people say, “I’m not creative. I can’t draw, I can’t sing.” In truth, the flow of creativity touches every human domain: the law, mathematics, politics, business, auto repair, sexuality, and everything else. A normal life entails telling jokes, solving problems, raising kids, and cheating on your taxes—creative endeavors, one and all. If you’re alive, you’re creative.

Techniques and standards aren’t intrinsic to creativity itself. They arise after the fact, so to speak. Creativity is an unstoppable process or life force that knows no standards or judgments. You can train yourself to direct this life force toward concrete goals that require specific techniques and that will be enjoyed by other people according to shared standards. But, to begin with, all you need is to engage in the process—to ride the life force, so to speak.

I started my adult life as a cellist, playing classical music. This entailed studying and performing canonic compositions written by other people in centuries long past. In common with most classical musicians, I became so involved with goals, techniques, standards, and judgments that my music making wasn’t actually creative. Creativity is like a tree, deeply rooted and growing immensely broad and high, with numberless branches and infinite leaves. Music is a branch of creativity; classical music a sub-branch; the cello as played in classical music a smaller branch still, nothing but a twig in the huge tree; and each adult cellist playing classical music is a bud, or leaf, or flower at the tip of a twig. As long as you’re still connected to the creative roots, to blossom at the tip of a twig is wonderful. But as a cellist, I plucked myself off the creative tree and became, in a word, dead: the dry, broken-off tip of a twig.

Over the years, I worked through these issues and managed to reconnect with the creative life force. This required that I give up my identity as a “cellist” (that is, as a twig). I had to let go of my technical standards, my narrowly defined aesthetic and professional goals, my judgments, my desire to please other people, and many other things that defined me as an individual. It wasn’t easy, I can tell you. But, hey, I found my way back to the roots of creativity.

Musically, my “not being a cellist” allowed me to become an improviser, composer, multi-instrumentalist, and singer. My current music is kind of tribal, primeval and beautiful, quasi-shamanic. It takes listeners on some far-out head trips. My “not being a cellist” allowed me to become a prolific writer of fiction and nonfiction, publishing a new book every two or three years and getting translated into French, German, Japanese, and Estonian. My “not being a cellist” allowed me to become a teacher, coach, and (to use a big word) healer, with a practice spanning the globe. My “not being a cellist” also allowed me to explore the visual arts, in particular drawing, photography, and video. In this article I want to touch upon photography as a creative outlet.

You get a lot done when you connect to the roots of creativity. If you’re open-minded and grounded, small efforts yield substantial results. So far, my photography has depended on a $300 compact camera, of which I use almost exclusively the automatic settings; the Mac’s photo editing program, iPhoto; an iPad Mini; and a free editing app called Snapseed. I used my iPad Mini to take all photos illustrating this article; I edited some of them with Snapseed.

Photography is a collaboration of many players: your eyes, brain, and heart; the environment around you; equipment and software; and technical knowledge. You don’t need to move to Paris to take good photos; the whole world is infinitely and permanently photogenic, there for you to enjoy and record. People have taken meaningful, touching photos of their kitchenware. And although it’s very tempting to think that technique and equipment are important, they’re secondary to your “working on yourself,” so to speak: being willing to take risks big and small, being willing to look, think, and snap the photo, without prejudging the results of the snap or worrying about what other people think of your creative efforts.

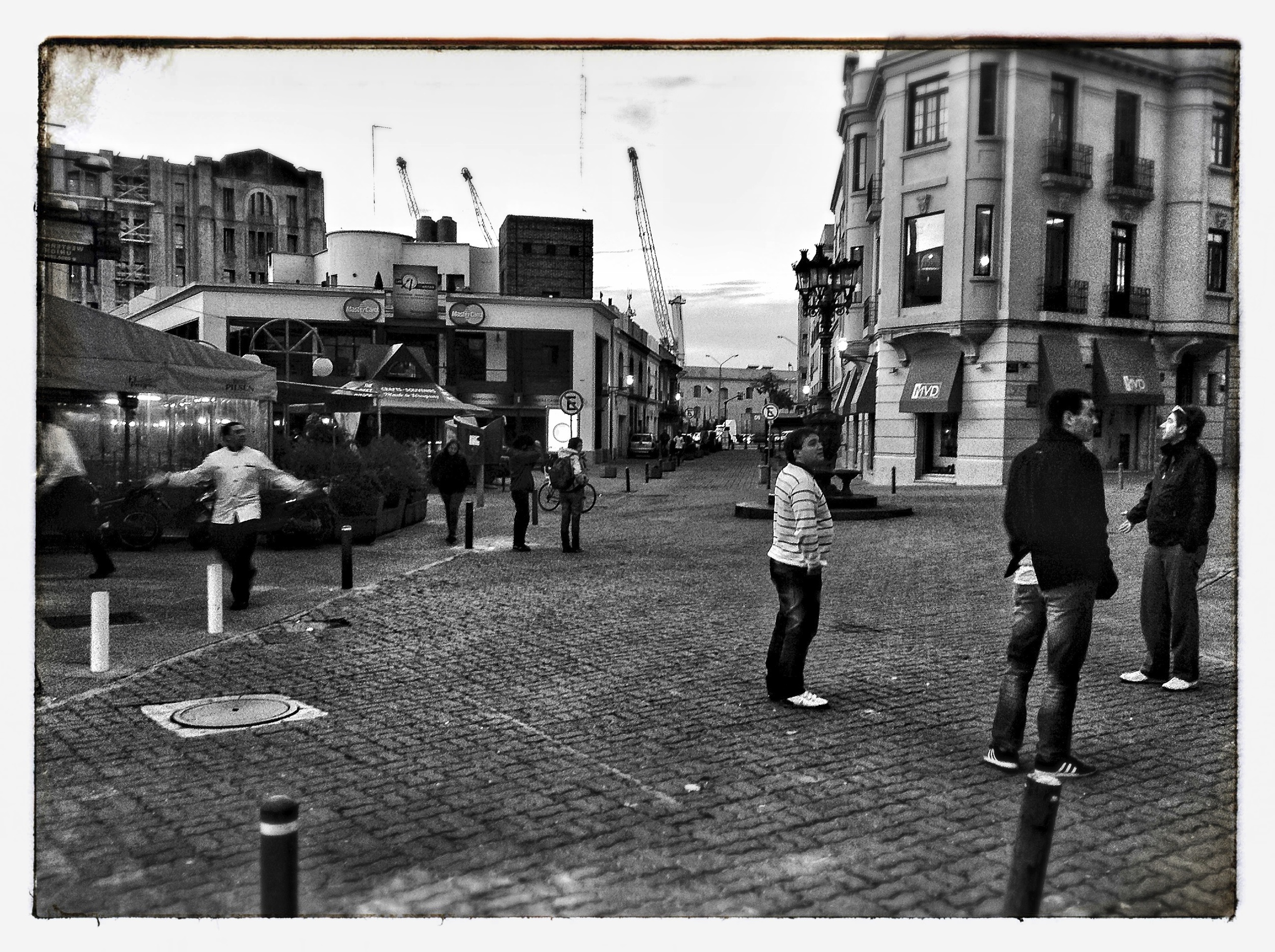

Every photo you take is a self-portrait—that is, a portrait of your own perspective, your choices and priorities. At a street corner there are so many details, so many things happening at the same time that thousands of different images could be taken in any one moment. But you take the one photo that you alone will take. Your presence in that street corner, your eyes and brain, your life experiences up to that moment determine your photo. As I see it, this is the core of photography: the “you” behind the camera.

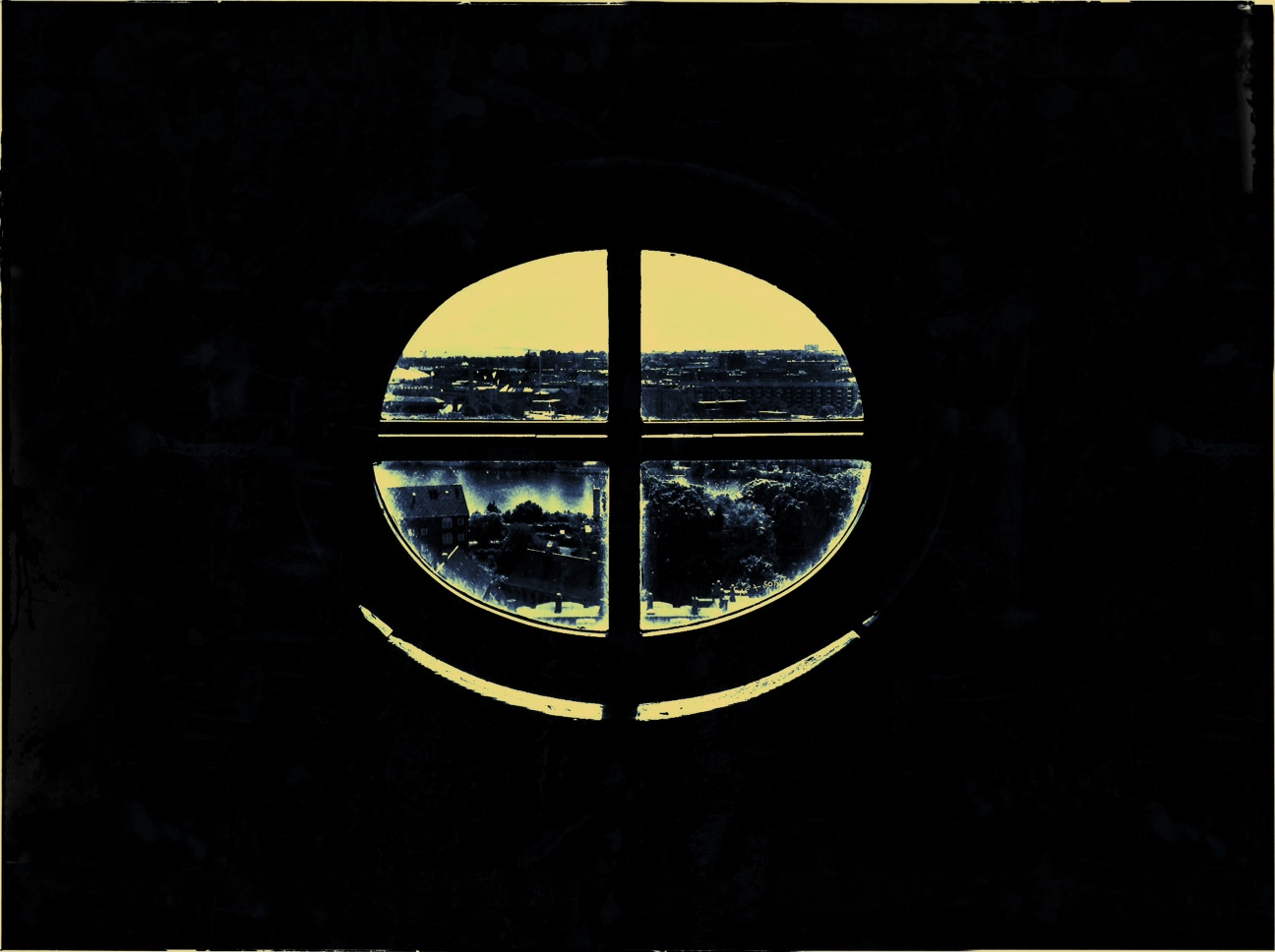

An iPad Mini is as good as any other piece of equipment to get you going, since the one thing that matters at first is for you to be willing to be present and to shoot the image. After you take a photo, or a dozen, or a hundred, you can go home and look some more, think some more, play some more. The Snapseed app is elegantly designed. In a minute you’ll know how to use it. And in two minutes you’ll discover that your original image can transform itself in multiple ways. It’s a bit foolish to think that a photo “must be true to reality.” Reality is so multidimensional that no photo can be true to it. Every choice you make as you take a photo—the where, the what, the when, the who, the how much—filters and alters reality in some way. Post-shoot, editing an image only continues the inevitable filtering process. Paradoxically, a good photo might capture some essential corner of reality and be true to it even as it filters and alters it in multiple ways.

Technique is partly a matter of absorbing information and practicing skills—with or without the help of a teacher—and partly a matter of learning from experience. Spend a couple of hours taking photos every week, and over two years you’ll take ten thousand photos in two hundred different settings. This gives you enough of a database to start exercising your discernment and making faster, deeper choices at the very moment of taking a photo. Ultimately, awareness is the one thing that counts the most. If you define technique as “trained awareness,” the pursuit of technique will become very enriching.