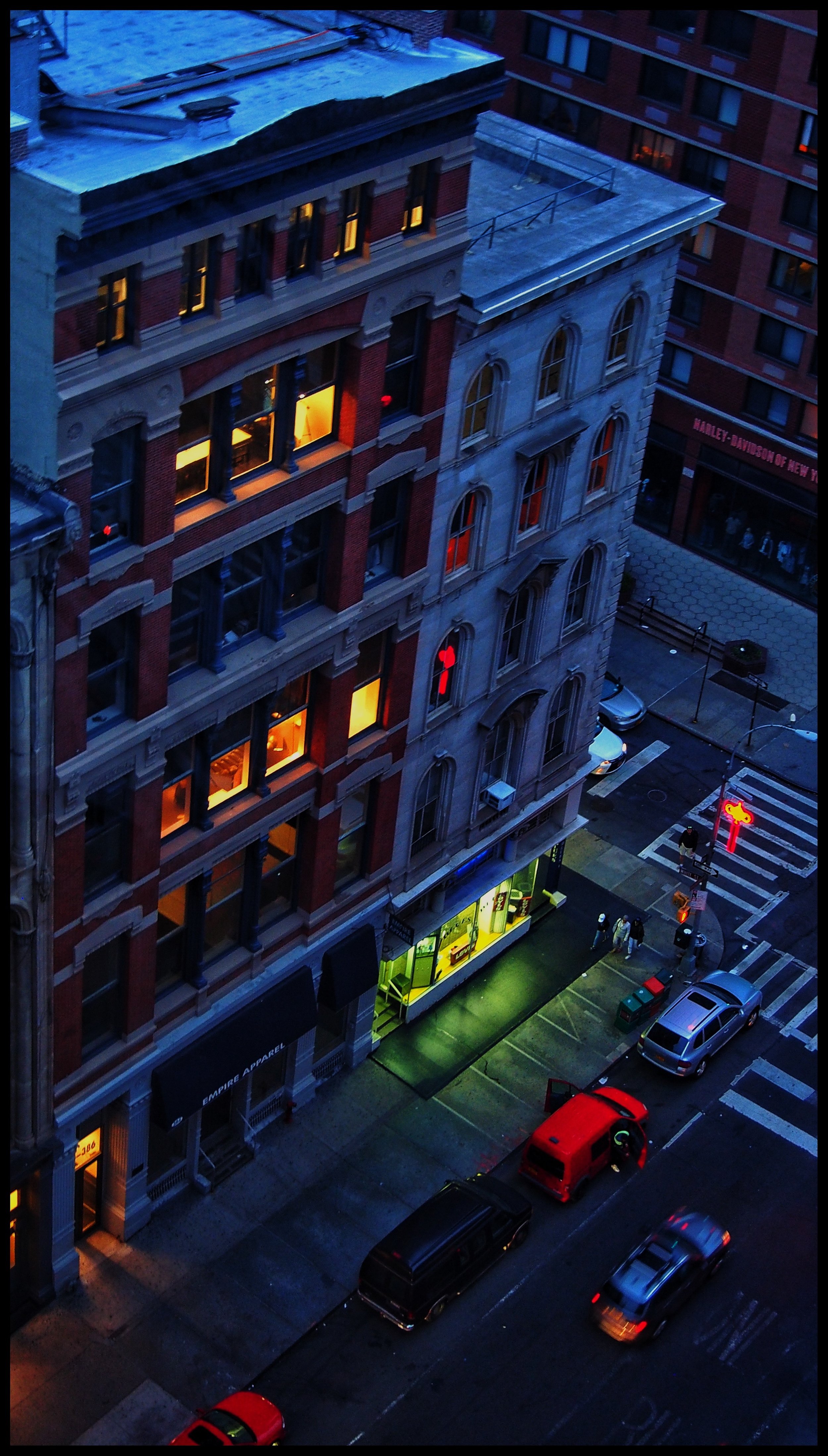

The photo above contains a tremendous amount of visual detail: buildings, windows, cranes, lights, repeated figures, extensions, colors of every hue. But your first apprehension of the photo is likely to be not of its details but of its overall shape, which triggers an entire visual, intellectual, and emotional response. For our purposes, it doesn’t matter whether you like or dislike the image; it only matters that, to begin with, you don’t see specific details but a sort of totality.

Look at some of the photo’s details. We can hardly recognize them as belonging in the original photo.

All the details in the photo interact with one another. The colors, for instance, interact among themselves; to our eyes, orange “behaves” differently if it’s next to green or next to blue. Some elements are repeated many times, others happen only once. We make something of this; we group repeated elements together and we contrast them with unrepeated ones, and by doing so we arrive at an understanding of the photo.

Traditionally, we like saying that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” In truth, it’d be more precise to say that “the whole is different from the sum of its parts.” The thoughts and emotions we have about the whole are of a higher and deeper level than the thoughts and emotions we have about each little part. The image in its totality triggers a story in our minds—a story we might tell in words or just in feelings, but a story nevertheless.

In the 1920’s, a group of German psychologists studying visual perception called this totality a Gestalt, which means “shape” or “form.” They posited that our minds prefer organization to disorganization, and coherence to incoherence; looking at anything, we’ll intuitively organize its visual information so that it makes sense to us. And our minds like capturing a whole before studying its details.

The notion of Gestalt proved popular, and over time it took a life of its own, spreading beyond the field of visual perception. A type of psychotherapy arose, called Gestalt therapy and concerning itself with the whole of the human being. Then a type of lifestyle arose, calling itself Gestalt Practice and incorporating movement and meditation. People now use the word Gestalt to refer to any system or context or totality; for instance, you might refer to the overall family dynamics of your crazy in-laws as their gestalt, and you don’t even need to use a capital “G” anymore.

Believe it or not, this post isn’t about Gestalt psychology or photography or in-laws. All of this was just an introduction, to give you some context for where my next bit of information comes from.

Here’s an image of a circle with a missing slice. Perhaps it reminds you of Pac-Man, of video-game fame. Or it gets you thinking, “pie chart . . . statistics . . . budget . . .” Or it comes across as a mere geometric shape in black and white.

Put three of these circles in juxtaposition. What do you see? No pie charts anymore; now there’s an “invisible” triangle, delineated by the missing slices of each circle. The triangle isn’t fully drawn, and yet our minds—which like organization and coherence—provide the missing lines and complete the triangle. It isn’t there, and yet it’s absolutely real to us.

To me, this image has symbolic power. Suppose the Pac-Men represents the body, the mind, and the soul. The white triangle that they form is life itself, the territory in which your existence unfolds. Body, mind, and soul can’t be separated without destroying the white triangle. Indeed, once you separate these parts they revert to being pie charts, geometric forms, Pac-Men.

The task for all of us is to be fully and wholly and entirely in the white triangle; to be complete, to be total; to be harmoniously integrated. It requires that we stay away from the Pac-Men. It’s very tempting to think that some problem of yours is physical in nature—tendonitis, to give an example. And it’s tempting to think that the physical problem has a physical solution. The thing is, your existence plays itself in the white triangle, in the interaction of all parts which have become transformed by their interaction. The tendonitis of our example is inseparable from thoughts, emotions, an aesthetics and a philosophy, a story, a Gestalt. Tendonitis isn’t a physical problem, but an indication of an existential situation.

It’s relatively easy to deal with tendonitis—or any other situation— if you deal with it inside the white triangle. What’s difficult is to enter the white triangle to begin with.

©2017, Pedro de Alcantara