Life is, oh so repetitive. How many breaths do we really take every day? Thousands. How many steps do we take? How many movements of jaw and tongue as we speak, argue, and exclaim? Thousands, thousands, thousands. Start thinking about it, and you’ll quickly conclude that it’s not possible to be alive if you don’t agree to a repetitive practice.

If you do any one thing twice, that counts as a repetition. Two or two thousand or two million, it’s all repetition. But two thousand times, with your mind focused on the action: wow. That is repetition! “To strive after, to attack, to rush, to fly!”

Adapted from etymonline.com.

To do a thing many times: normal, banal, inevitable. To pay attention to a thing as you repeat it thousands of times: extraordinary. Attention is the mother of meaning. Your repetitive breath becomes meaningful when you pay attention to it. This isn’t free of risks, as you might become terribly self-conscious about ribs, throat, diaphragm, and—and oxygen. You’ll hyperventilate and pass out, guaranteed. Attention is the mother of dyspnea, hyperpnea, and oligopnea.

But I digress. Something doesn’t truly exist until you pay attention to it. And something truly exists when you pay attention to it. The something may be a fictional character, an abstract idea, or a voice in your head. It exists by occupying your psychic territory, and if you remain attentive to it over time, it’ll develop and grow. The monster becomes extremely strong if you think about him again-and-again-and-again. It doesn’t matter if the monster was born in the Maternity of Your Santa Cabeza. It’s a giant.

Repetitive practice creates monsters, for sure. But it also creates marvels.

You look at the face of your own child tens of thousands of times. You see the growing child differently from moment to moment, from year to year. The child is always changing, and so are you. On occasion, or often, or very often, you look without seeing. You may be “looking at your feelings” rather than “looking at the child.” But, all counted, you look at your child’s face for the equivalent of two full years, spread out over eight decades. Thirty thousand psychic snapshots, a repeated practice of unfathomable import (or, as Carl Jung used to say, “ein hellava Ting zu Du.”).

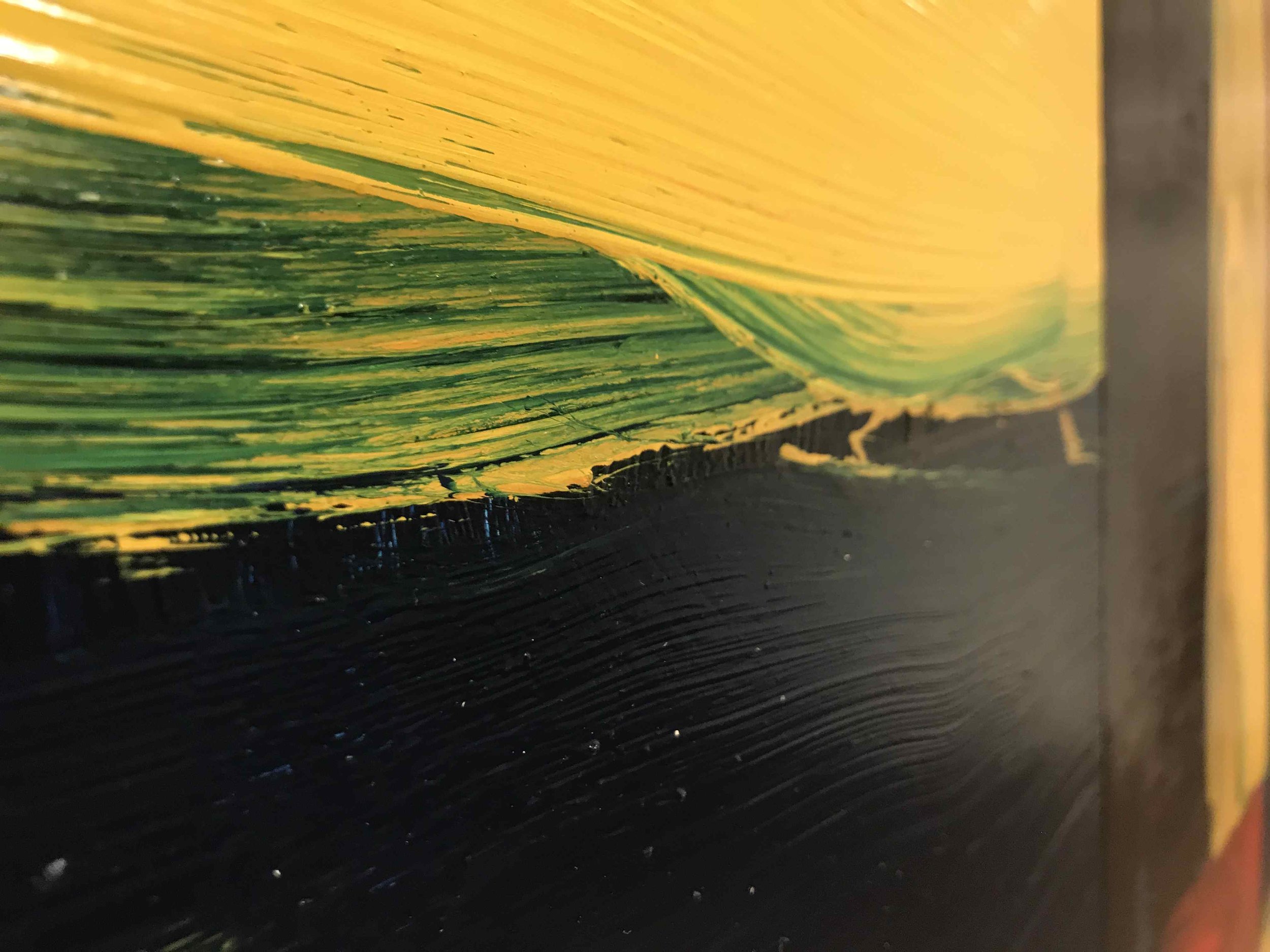

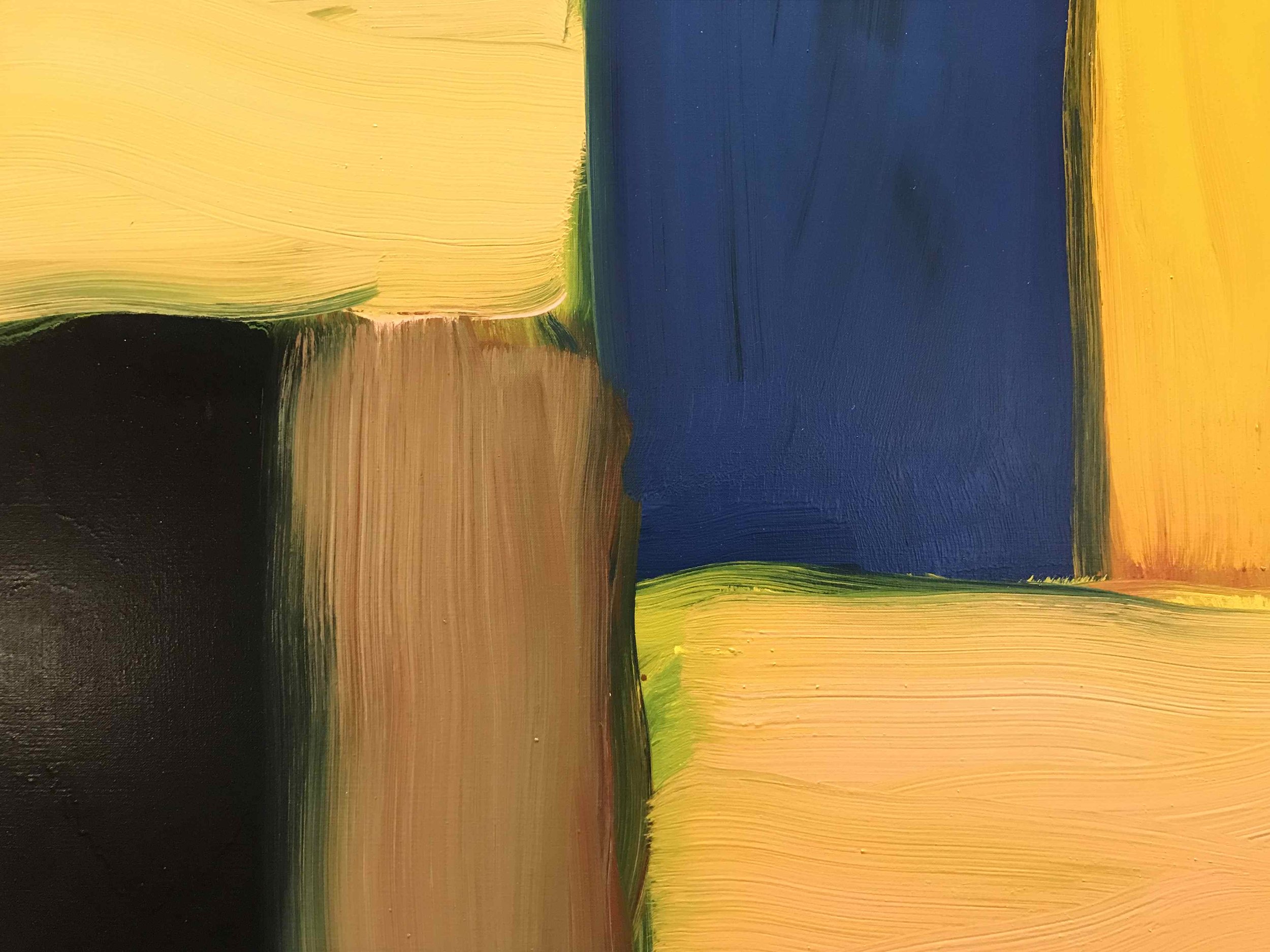

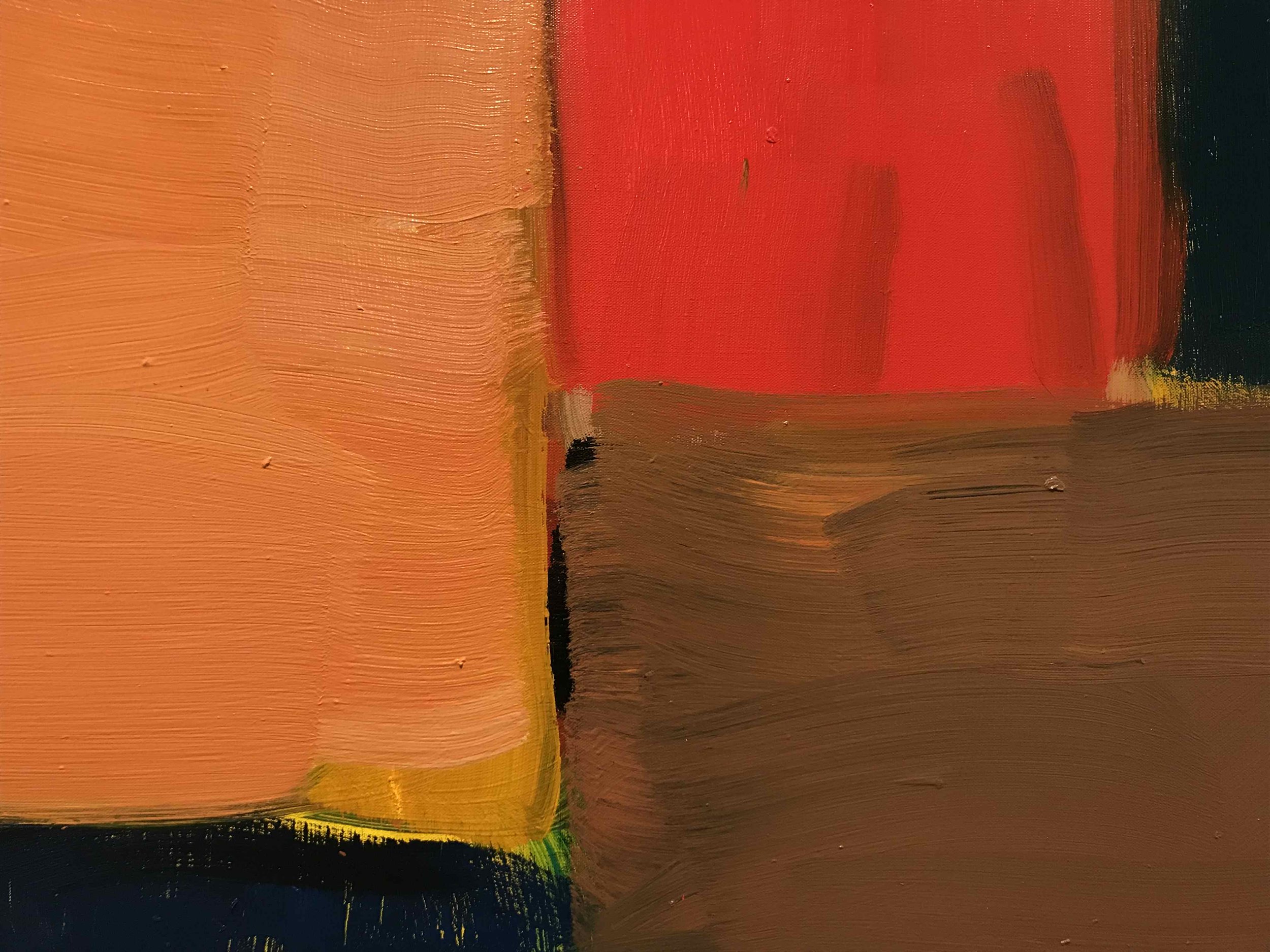

The average museum goer looks at a work of art for less than thirty seconds before moving on. How much information do you gather about something in thirty seconds flat, as opposed to two years spread out over eight decades? Look at the painting for longer; look at it more often; return to the museum or gallery and look at it in the morning and in the afternoon, before you eat and after you eat. The painting doesn’t behave the same when you’re hypoglycemic and when you’re over-caffeinated.

Go back, look again, go back, look again,

look for a while longer, look and stay looking.

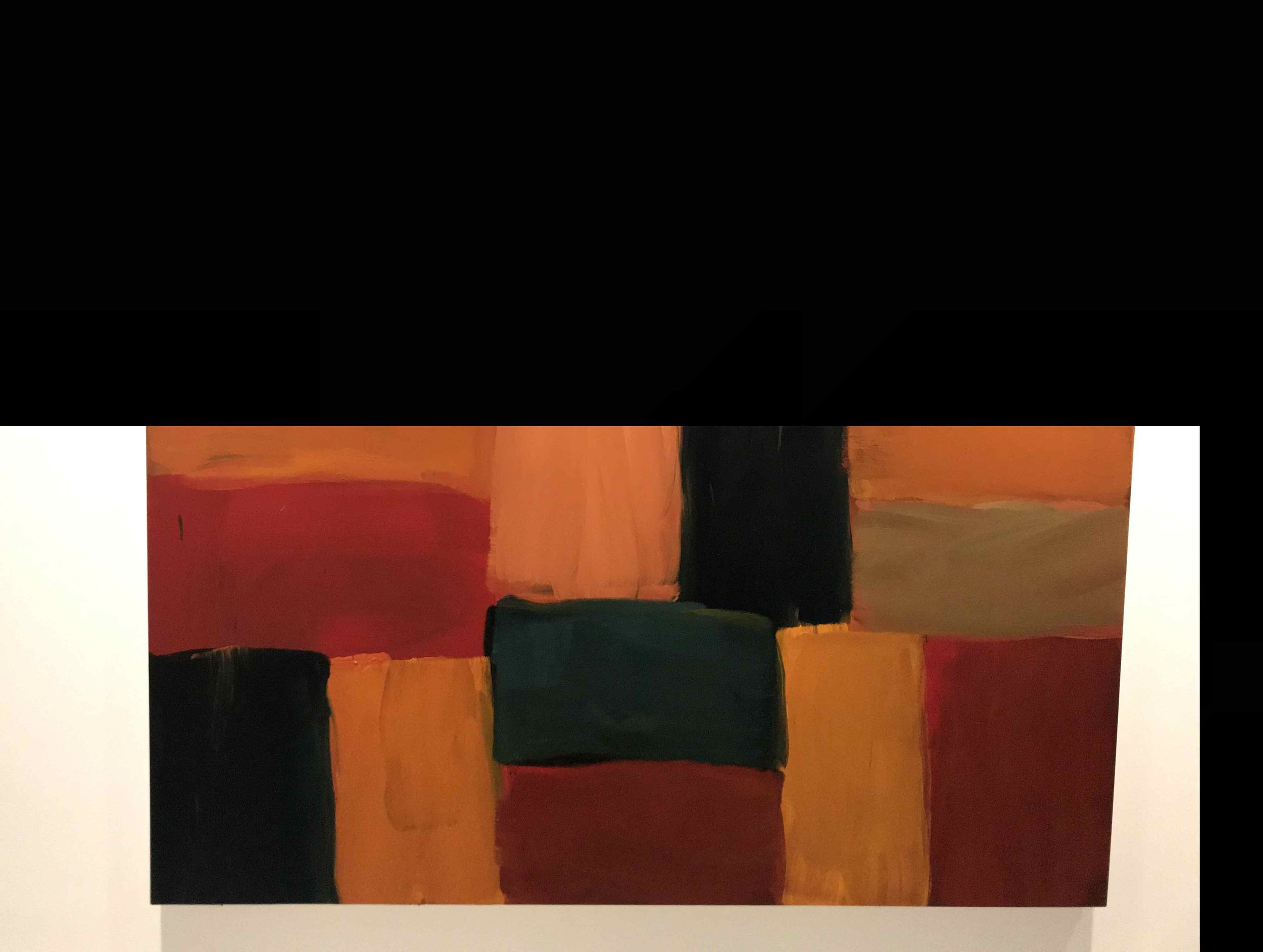

An art gallery near my home had a show of paintings by Sean Scully, the great Irish-American artist. I visited it six times, staying between 25 and 40 minutes each time. There were about 18 paintings in the show. Let’s say three hours of visits all counted, 18 paintings, ten minutes per painting. “I looked Sean Scully in the eye. We didn’t blink.”

You don’t have to go to actual museums. You can look at any one thing, one beautiful thing in your home, again and again many times: a book, a rug, a piece of carpentry, the window giving out onto the garden. Or a wall of street art in your neighborhood.

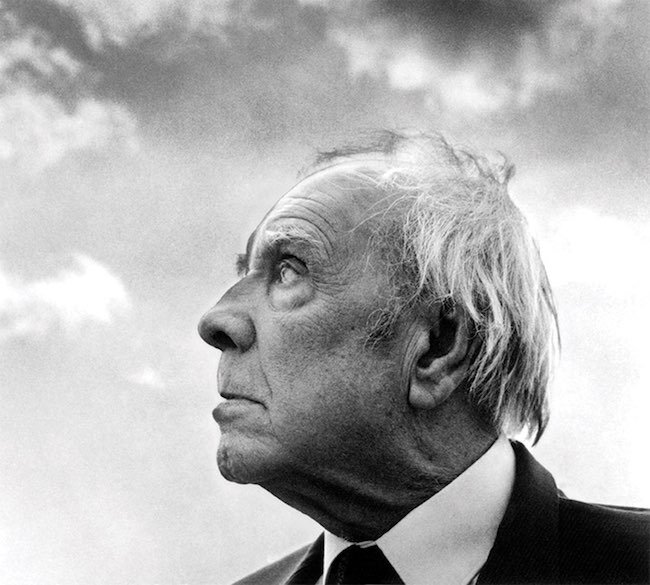

I’m a big fan of Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentinian poet, essayist, and short-story writer. I’ve been reading the same few short stories again and again—I mean, some of his stories I’ve now read thirty or forty times.

The information digs little pathways in your brain, and starts to influence your life and to change it. Symbolically if not biologically, the repeated information becomes embodied—that is, it becomes part of you. You look at a guy walking down the street, and you see his embodied information, the result of his repeated practice. This principle is easy to assess if you limit the observation to something like athletic activity: you see the guy’s biceps, and they bulge, do they ever. But the principle is operative across all fields of existence. The intellectual’s repetitive think-hard practice bulges, too! Does it ever!

Exact repetition of a gesture doesn’t happen often. Some aspect of the gesture is repeated, another aspect is varied. But in our system, this still counts as repetition. No two of my two thousand visits to the Place des Vosges were ever exactly alike, and some visits were remarkably different from the average visit. It doesn’t matter; variety is a fine component of repetitive practice.

Repetitive practice isn’t based on “I should do this,” but on “I want to do this.” Pleasure, integration, paradise. Repeat after me:

Pleasure, integration, paradise.

Pleasure, integration, paradise.

Pleasure, integration, paradise.

Pleasure, integration, paradise!

©2021, Pedro de Alcantara