We all know the power of the first time: the first memory, the first kiss, the first trip in an airplane, the first public performance, the first death in the family . . . Every day we do many things for the first time, although it’s not every day that we notice or cherish the first-timeness of the things we’re doing for the first time.

This is the first time I have used the expression “first-timeness,” which of course Goethe plagiarized from me when he wrote Erstezeitlichkeit und die Fünf Bananen in 1804.

Fünf Bananen

But I diverge (Bananen). Today I’d like to talk about some of the first-time things that jostle your awareness and mark you forever and ever, the things that open up your mind, which means the things that proved to you that your mind was closed and you didn’t know it.

In my youth I took lessons in the Alexander Technique with a famous teacher, a significant player in the history and traditions of the profession. Innocently I had imagined, assumed, and determined that the famous and beloved teacher was necessarily a competent expert. Right? Fame, tradition, history, Bananen, you name it. One day she saw me go into a squat to pick up my shoes, and she stopped me cold in mid-flight. “Never do that,” she said sternly. “It’s wrong.” And, pling ka-boom cha-cha-cha! I suddenly understood that she was literal-minded, dogmatic, and judgmental, and I suddenly understood that I had been rather silly in my assumptions. This happened more than 35 years ago, but the experience of the ka-boom has stayed with me, as if I had undergone a secret ritual initiating me into belated incipient adulthood. Believe it or not, Goethe calls it “Verspätet einsetzendes Erwachsensein,” and several characters in his Faust / Eine Tragödie undergo similar rites of passage.

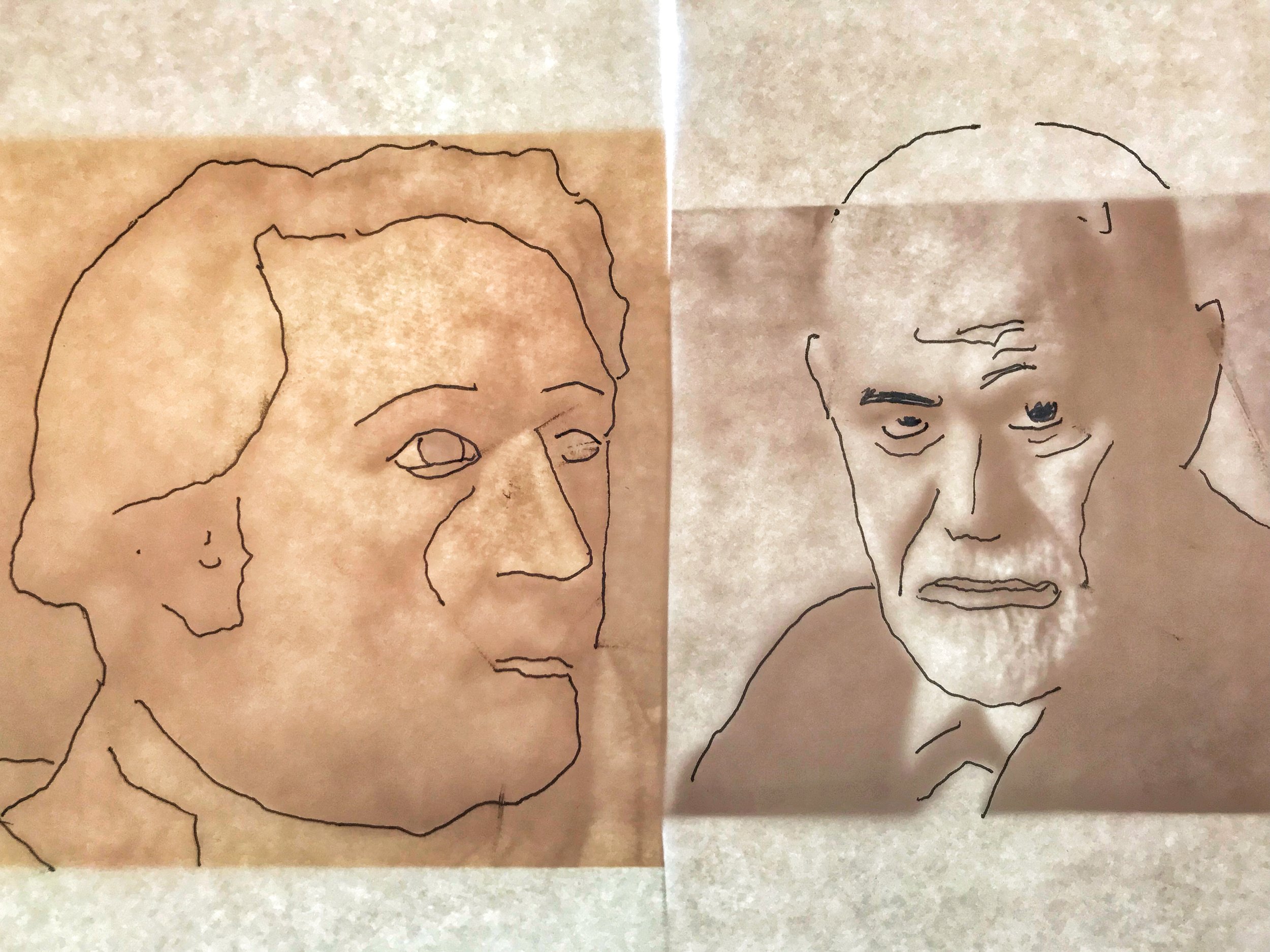

The moral of the story? Make no assumptions. Among the many assumptions you’re better off NOT making, don’t assume that so-and-so is like this-and-that (or, as Sigmund Freud said on the centenary of Goethe’s death, “So-und-so ist wie dies und das.”)

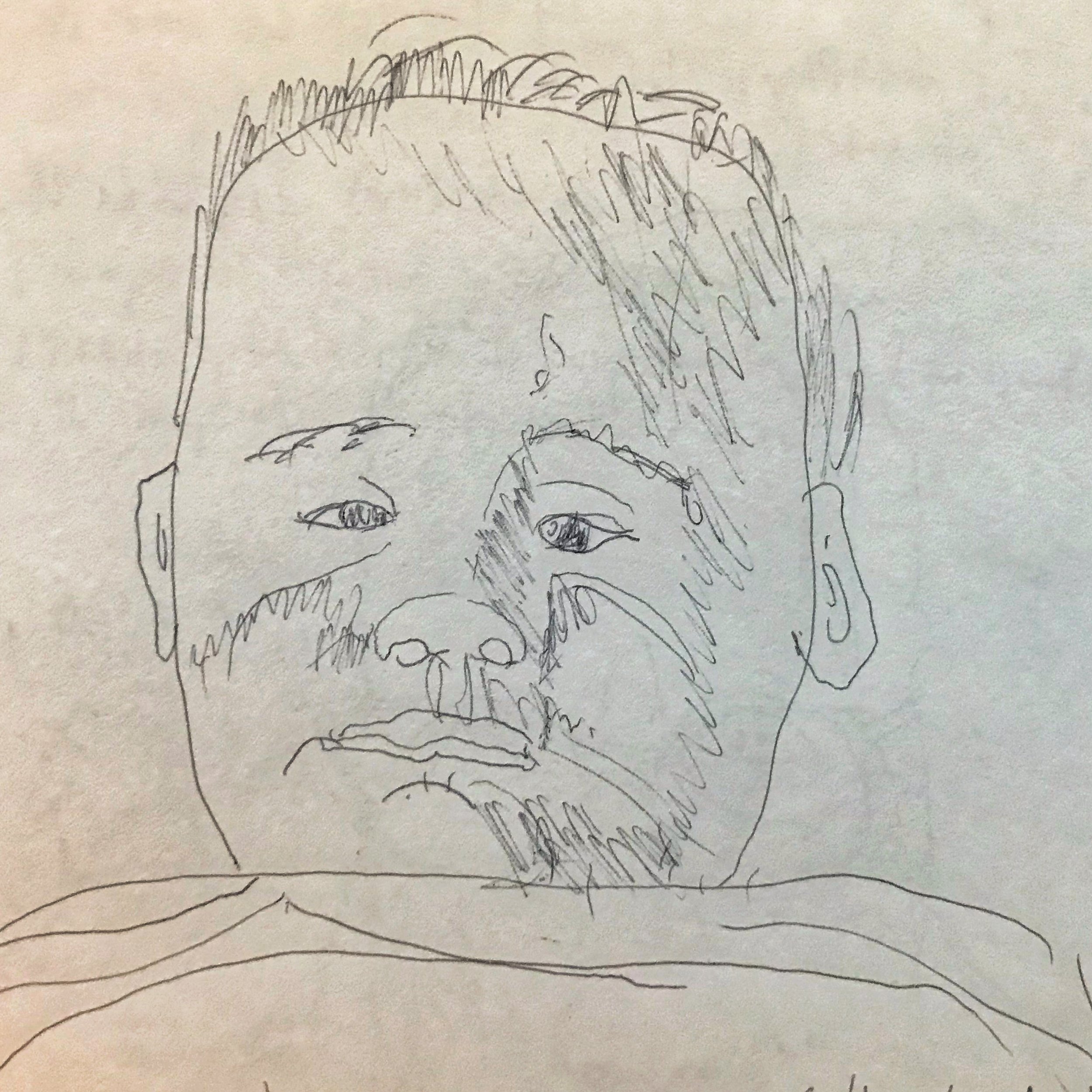

For several decades I lived with the certainty that I had no talent for drawing. I could prove it, absolutely! All I had to do was to draw a crappy stick figure and say, Look! I cannot draw! Roughly 15 years ago, circumstances led me to decide to do one little drawing every night before going to bed. I started by copying photos of family members. The third night, my little drawing of my nephew as a baby came out . . . well . . . kinda super-excellent. I had to accept that I had long lied to myself, and that I had believed the lie with all my heart. The baby of hard truth now stared me in the face: I can draw. I think this was the first very substantial experience of catching myself in the act of telling-a-lie-to-myself-about-myself, which Freud called “Ego Schmego Hasta la Vista Amigo.”

The immoral of the story? If you need to tell a lie, don’t tell it to yourself about yourself! Tell it to Freud about Goethe! Or the other way around! “Von links nach rechts, von rechts nach links!”

I used to think of myself as an intellectual. Some 28 years ago, a participant in one of my workshops told me, “Pedro, you’re the archetypical intuitive.” I resented her, because—hey, intellectuals rank higher than intuitives in the DM-ID: A Clinical Guide for Diagnosis of Mental Disorders in Persons With Intellectual Disability. A real book, I swear! You can buy it on amazon.fr for 1500 euros, and I’m not making this up! It took me many years to embrace the clinical fact that intuition was my primary mode of functioning. But my point is that there was a first time when I heard the news, a shocking first time, an upsetting first time. I wish I could send a valentine to the girl who brought it to my attention, although of course I don’t remember her name, her face, or her Schweinshaxe.

And the amoral of the story? Listen to the herald bringing you good news, shocking or upsetting as the news may be. But don’t listen to what Goethe says about Freud,* because you risk going quite kuku in der Keke.

*”Du bist Bananen.”

©2022, Pedro de Alcantara