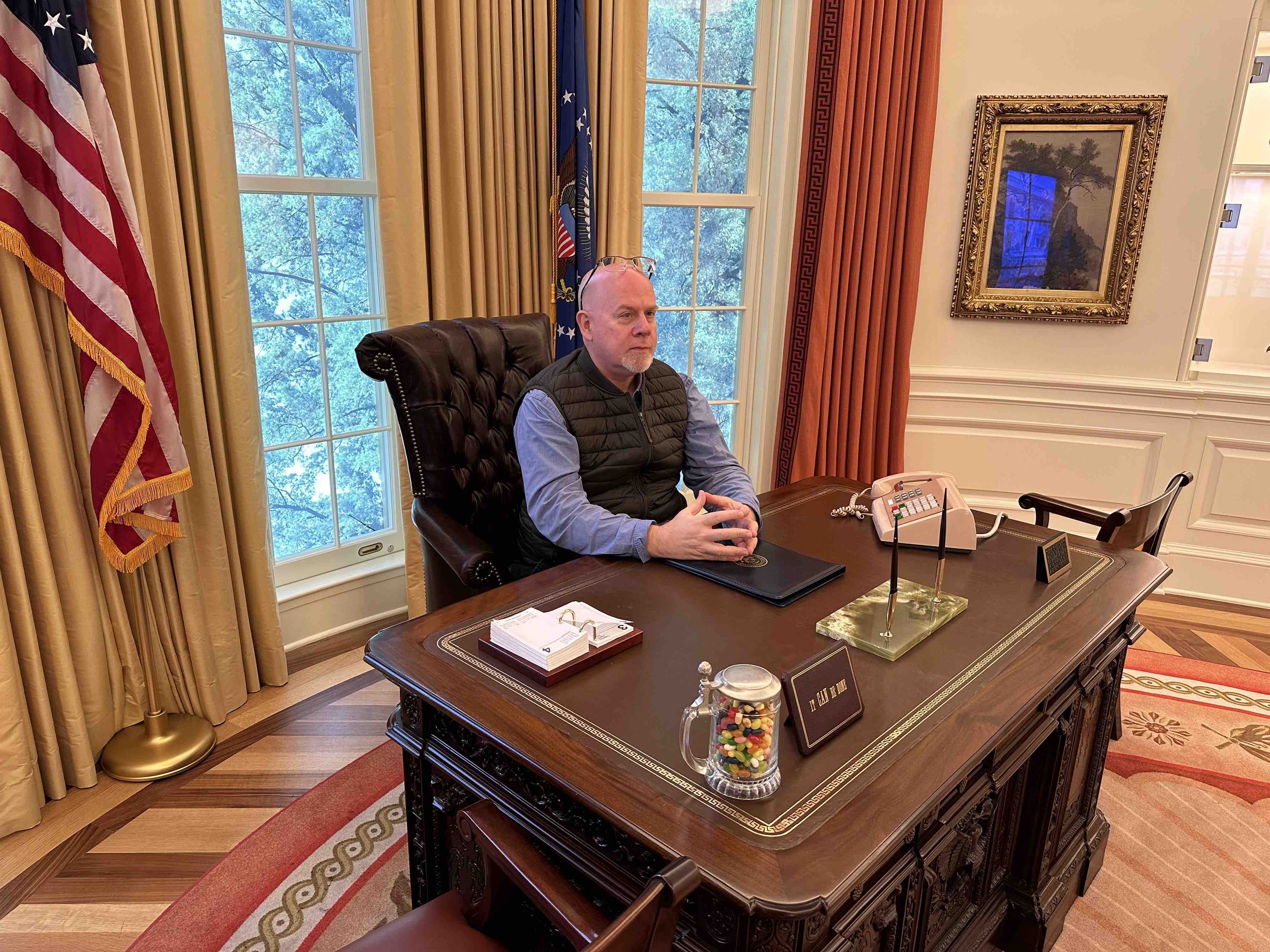

You read a book, for instance, assigned to you as schoolwork or as part of your Book Club. And inevitably you become the book’s co-author. You understand some bits but not others, you pay attention to some characters and events but you let your brain rush through borings passages, you identify with a secondary hero and you want to strangle one of her enemies. You analyze and digest the book, which becomes yours. Strangely and amazingly, the book that you’ve just read is completely different from the same book that your Book Club friends or schoolmates read. You can hardly believe it. How could they have missed so much of it? How could anyone not hate the ending? Are your friends completely crazy?

No, they simply co-write the book, “their book,” in their own way.

This process, which I’m going to call Transformative Projecting Subjectivity, is central to life. We co-write books and films by the way we respond to them. We interpret events. We respond to people, who become screens on which we project our own stories and likes and dislikes; and our projected stories “are” the people that we meet and interact with. We see the world with our own eyes, our little eyes, our big eyes, our irritable or distracted or keen or childlike or cynical eyes. And most of the time we aren’t alert to how we’re subjectively creating our individual world. We don’t know it, but we’re completely crazy.

Let’s go back to the imaginary book of our example. It exists as a material object, as a Manifestation of the Book Principle that unites every book written in history. It exists as part of a chain of imagination, creative effort, revision, editing, publishing, and distributing. It comes in multiple editions—paperback, hardcover, Kindle, audio, smoke signals. It might be translated into several languages. And it means something subjectively different to every reader who’s ever leafed through it, or studied it in depth; it also means something to the readers who have a faint inkling of what the book is about but who resolutely refuse to read it. The book is charged with every readerly emotion; the book is the recipient of every reader’s own story. The book is a shapeshifter, incessantly transformed by its encounter with each reader. Some books have had a long life, taking part in billions of encounters, which are billions of transformations and interpretations.

I asked Google to translate something into Persian for me: “I, book, am billions.” I’ll credit Rumi with the sentiment, although this is of course a lie. Rumi and Google have never met.

Books are just an example. We are the interpretive co-authors of all objects, all events, all situations, all words, all statements; through our perceptions and projections we’re co-creators of “everything, and everything else too.” Necessarily, we are the co-authors and co-creators of the people we meet; and other people, meeting us, create infinitely varied versions of us.

Human beings are complex and multilayered. The last simple human being was an amoeba who lived in Inner Gondwana five hundred million years ago. Since then, complexity has taken over. Contradiction, paradox, conflicting impulses and appetites; personalities that change from Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde at the drop of a pacifier; strengths and weaknesses indistinguishable from each other . . . we’re Veritable Dagwood Sandwiches, splattering the world with our ketchup

From my favorite site, www.etymonline.com:

In some of the earliest uses it’s described as an East Indian sauce made with fruits and spices, with spelling catchup. If this stated origin is correct, it might be from Tulu kajipu, meaning "curry" and said to derive from kaje, "to chew." Yet the word, usually spelled ketchup, is also described in early use as something resembling anchovies or soy sauce. It is said in modern sources to be from Malay (Austronesian) kichap, a fish sauce, possibly from Chinese koechiap "brine of fish," which, if correct, perhaps is from the Chinese community in northern Vietnam [Terrien de Lacouperie, in "Babylonian and Oriental Record," 1889, 1890].

But I digress. I’m trying to say that every person who’s ever met you has fabricated a version of you. It doesn’t matter if the “other” has met you in passing or closely, professionally or personally, at home or at school, in the back of a poorly lit, drafty, moldy church or in the lobby of a shopping mall in Inner Gondwana. The “other” has partly perceived and partly invented you, and you’ve done the same to the “other.” You might struggle to recognize this fabricated impression as “you,” but, but, BUT! yes, it’s “you” in some difficult-to-explain way. Someone finds you clever and attractive, and someone else finds you tiresome and ketchup-y. They’re both right!!!!! They’re your co-authors, writing and interpreting you; and for them, you definitely are this entity that they see, hear, smell, touch, and sometimes taste.

It seems useful, I’d say, to accept that you’re complex and multilayered, and that other people are also complex and multilayered, and that human interactions are Subjective Dialogues of Complexities with Elements of Perception, Fact, Projection, Imagination, Filter, Perspective, and Taste All Mixed Up. Try to convince the “other” that You’re Not What They Think You Are, and the “other” will then know for sure that you really are COMPLETELY CRAZY.

©2024, Pedro de Alcantara