My wife knows me. That makes sense, right? I mean, she can tell when I’m squirming, or floundering, or squiggling, or threshing, or prevaricating, or gerrymandering, even if I’m sitting still and looking relatively normal. The other day she saw that something was afloat, or sinking, or—Pedro, leave the Thesaurus alone and tell me what’s going on.

I’ve been working on a piano method for four years, and it’s now under contract, with a deadline. Concepts, exercises, compositions, video clips. Did I tell you that the project is big? I explained to my wife that, besides everything else, I couldn’t choose among a number of solutions for a structural problem deep inside the project. I tried to describe the problem and some of its solutions, and my wife bypassed the intricacies and diagnosed my condition: “You’re suffering labor pains.”

The light bulb went on, the penny dropped, and the dog wagged its tail. Thanks to my wife I had understood the biological and symbolic dimension of project management. It’s called “conception, gestation, delivery.”

Before you become attuned to the possibility of a project, it exists on an immaterial plane out of reach of your intellectual grasp. Let’s call it “God’s imagination,” which of course is eternal and infinite. It encompasses all projects, including—for instance—performing the entire Bible as a one-man Kabuki show, or floating a horizontal Empire State Building along the Suez Canal, or eating five kilos of chocolate in one sitting just to see what happens (“apotheosis”). From that database, a project “comes to you,” often when you least expect it, sometimes catching you in a bad moment. On Saturday, May 14 2017, I was practicing the piano at Studio Bleu in central Paris, struggling to get the brain and the fingers to make friends, when I heard a voice. (I swear I did.) “Pablo, why don’t you write a piano method?” “My name is Pedro.” “Of course, my apologies. Pedro, why don’t you write a piano method?”

Conception! The project had passed from the immaterial to the brains-and-fingers, from the universal to the individual, from unimaginable to imagined. I was elated. “Thanks, Joe!” “My name is G-d.” “Of course, my apologies!”

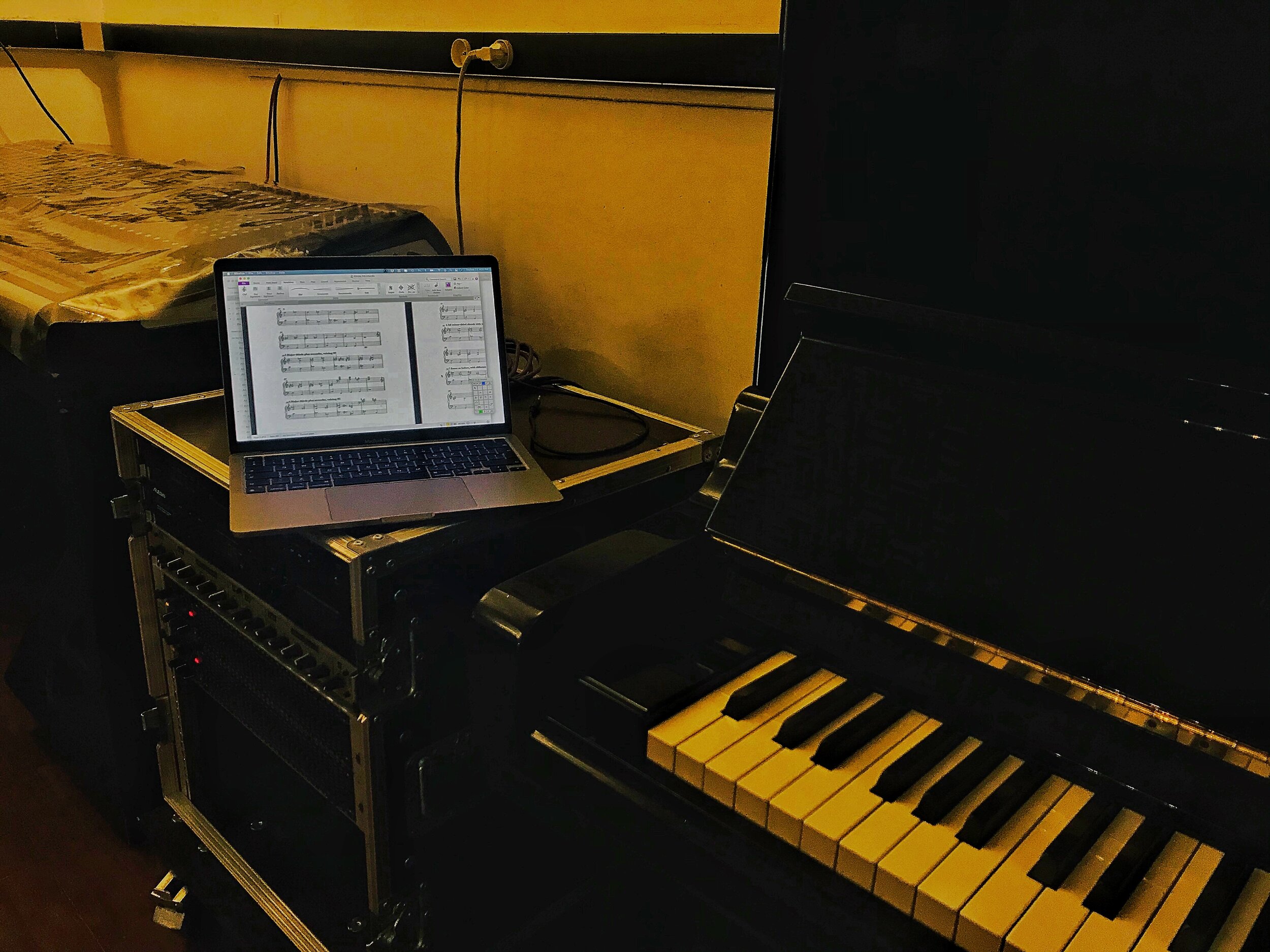

Photo by Mônica Marcondes Machado

Like in the baby-generating domain, project conception is an amazing and incomprehensible wonder. I immediately started getting ideas and insights about the creative processes of playing the piano. It was a revolution in my music work. I’m not saying that I suddenly started playing the piano well, only that I had found a new path to explore. I’ll be pretentious and name it “the true path.”

Then came the gestation period, the appetites (five kilos of chocolate), the morning sickness, the growth of that stranger inside you, the deep meditation. Gestation meant studying, practicing, reading, watching, practicing, sharing, teaching, learning, practicing, performing, writing, editing, revising, discarding, despairing, and marveling. If a project needs two months, it’ll take two months; if it needs four years, it’ll take four years. Mosquitos and elephants don’t have the same gestation period.

“When is it due?” According to my contract with Oxford University Press, the baby is due on April 1st (this April 1st, not next year’s; today; TODAY!). That means delivery of the final manuscript, plus supporting materials, plus blood and guts. The baby will be late. The baby is lingering and malingering inside the cocoon. The baby has structural problems that need intrauterine laser surgery. The baby enjoys inflicting labor pains upon its hapless famother (you know—the amalgamation of father and mother, Isis and Osiris, tomato and mozzarella). The baby—

I love my baby. Do I really have to let go of it?

©2021, Pedro de Alcantara