Why do we breathe? To survive, and also to express our thoughts and emotions.

Why do we tell stories? To express our thoughts and emotions, and also to survive.

Our need to tell and hear stories is universal; like breathing, it’s a deep and urgent need. Some of the themes in our stories are also universal: hope and fear, travel, adventure and discovery, death and loss, and above all love. The stories themselves, however, are not universal, but specific to a certain place and time. And our reactions to the stories we hear are also individual. Ten of us are sitting together in a room, and someone tells us a story. Listening with our personal filters, we retell the story to ourselves in real time—we transform what we hear even as it's being told, and the story that takes shape in our heads isn’t the same as the story taking shape in the head of the person sitting right next to us. The universal becomes individual; ten listeners, ten different stories.

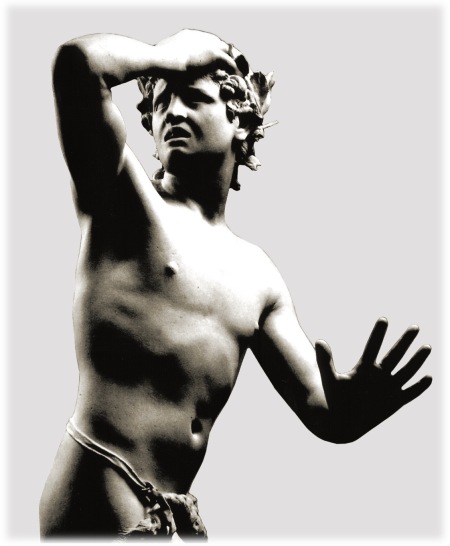

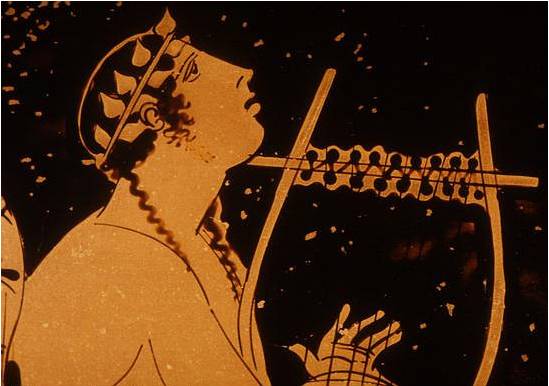

Let’s take Orpheus and Eurydice. It can be called a story or a legend, a myth or a tale; its characters are both wholly imaginary and very, very real. Orpheus is such a fine musician that, with his lyre and his singing, he can tame beasts and make stones cry. He meets Eurydice, they fall in love, they marry. A serpent hidden in the grass bites Eurydice’s ankle, right after her wedding to Orpheus. She dies. Orpheus is heartbroken and decides to descend into the underworld to bring her back. He will have to deal with Charon, who ferries the souls of the newly dead across the river of darkness. Then Orpheus will have to deal with Cerberus, the three-headed dog who prevents souls from departing. And Orpheus will have to convince the underworld’s overlords, Hades and his wife Persephone, to let him retrieve Eurydice. He sings to each in turn, and they all fall under his spell. Hades tells Orpheus that he can take Eurydice with him, but on one condition . . . don’t look back. Walk ahead of Eurydice, and don’t look back at her until both of you are back in your world.

And Orpheus will look back, and will lose Eurydice forever, and will go mad with grief, and will die a horrible death.

The first telling of this story is more than two thousand years old. It’s an amazing thing: a story and its characters staying with humanity forever, and forever being transformed by storytellers and listeners. It can only happen because the story’s themes are universal: love and loss, death and what happens after we die. We really want to know about it. But we each want to know in our own way. So, let’s tell and retell the story, until it’s ours.

Over the millennia, the story has been told in every language and in every artistic medium. Paintings and drawings, film and theater, poems and songs, mime, stop-motion animation, folk-rock opera, comic books, everything.

The Roman poet Ovid told of Orpheus in Metamorphoses. Let’s be silly and take Ovid’s beautiful Latin (which we don’t speak) and get Google Translate to retell the story for us.

- 10:1 Inde per inmensum croceo velatus amictu

- 10:2 aethera digreditur Ciconumque Hymenaeus ad oras

- 10:3 tendit et Orphea nequiquam voce vocatur.

- 10:4 adfuit ille quidem, sed nec sollemnia verba

- 10:5 nec laetos vultus nec felix attulit omen. . . .

- 10: 1 Then the saffron mantle

- 10: 2 marriage to the edges of the air unmeasured Ciconian

- 10: 3 tends to the voice of tuneful Orpheus.

- 10: 4 present indeed, but not the usual words,

- 10: 5 or happy faces, no happy omen. . . .

Many stories come across as incomprehensible or strange or twisted or illogical. It’s inevitable. Stories bridge the gap between the dreamworld and the world of coffee and croissants—two worlds, two mutually exclusive languages. It’s okay not to understand a story. It’s probably better not to understand it too well. It’s good that the story is told “in a foreign language,” be it Latin or Google.

The composer Claudio Monteverdi was one of the creators of opera, that peculiar mixture of theater, dance, and music. He composed an opera about Orpheus and Eurydice, first performed in 1607. Do you like strange? Watch this clip. Do you like even stranger? Watch it a second time, with the sound off!

Monteverdi’s opera is still being produced all over the world, 400 years after he composed it. Why? The theme of the story is universal. We really want to deal with our hopes for love and our fears of loss and death. And it’s okay if we see and hear, on newfangled YouTube, a modern-day recreation of a Baroque artifact which back then was a reinvention of a Classical Greek artifact.

The French film maker Jean Cocteau produced a trilogy of films centered on Orpheus, or a version of Orpheus, or Cocteau’s projection of his own 1950s Frenchness onto the Orpheus matrix. Cocteau’s Orpheus is a poet. Watch how he enters the underworld in this famous scene. I chose the version without subtitles, to help the non-French speakers among you to absorb it all emotionally rather than intellectually. Remember, strange is good!

Watch a bunch of Uruguayans do a dance-theater piece about Orpheus. It’s all strange and touching . . . hope and fear, love and death. I’m the cellist, sitting back there and strumming my cello as if it’s Orpheus’s lyre. And, no, I’m not Uruguayan. It doesn’t matter.

I’ve spent the past three or four years composing a cycle of songs and instrumental pieces retelling Orpheus and Eurydice in my own way. Orpheus sings, plays the piano and the cello; to Eurydice I gave birdsong, and she whistles all her lines. Would you like to hear a scary and strange song where Charon, the ferryman, speaks for all the broken souls of the underworld? Click below. Listening with headphones would make your fear more palpable.

And would you like to watch and hear a strange and beautiful thing, hinting at the whole love story and the dread of looking back? I bet what you'll hear and see watching the clip isn't what I put in there, but what you put in there yourself.

©2017, Pedro de Alcantara