Dumb guy, never changes his mind.

Silly guy, changes his mind all the time.

Hello, my name is Pedro!

One way of understanding a human being is to get a sense of how much he or she changes opinions, over what subjects, with what intensity, how quickly or slowly, how often. We all know someone who seems never, ever to change opinions, attitudes, and habits . . . stone brain in a granite body. And we all know someone whose opinions and attitudes are like fruit flies over a pile of compost. Flit, flit, flit, flitz blitz I’m at the end of my wits I call it quits!

I moved to Paris in 1990, and I’ve lived here since. During my first few years, I busied myself researching and drafting my book Indirect Procedures: A Musician’s Guide to the Alexander Technique. Circumstances favored me, and the book was nicely published by Oxford University Press in 1997. In 1994, my French colleague Annie Moteï was contacted by a French publisher who wanted to add a book on the Alexander Technique to his catalogue. Annie wasn’t interested, but knowing that I was happily absorbed in the process of writing she recommended me to the publisher.

The guy, Monsieur Dangles, sent me a letter and a proposal.

As Jimmy Stewart would have said, “Wait a minute!” I mean, my French was rudimentary. Prepositions! Conjugations! Vocabulary! Idiomatic expressions that didn’t make any sense! I think some Parisians would have considered my French back then as nothing but “lingerie de foie gras.”

I accepted M. Dangles’s proposal.

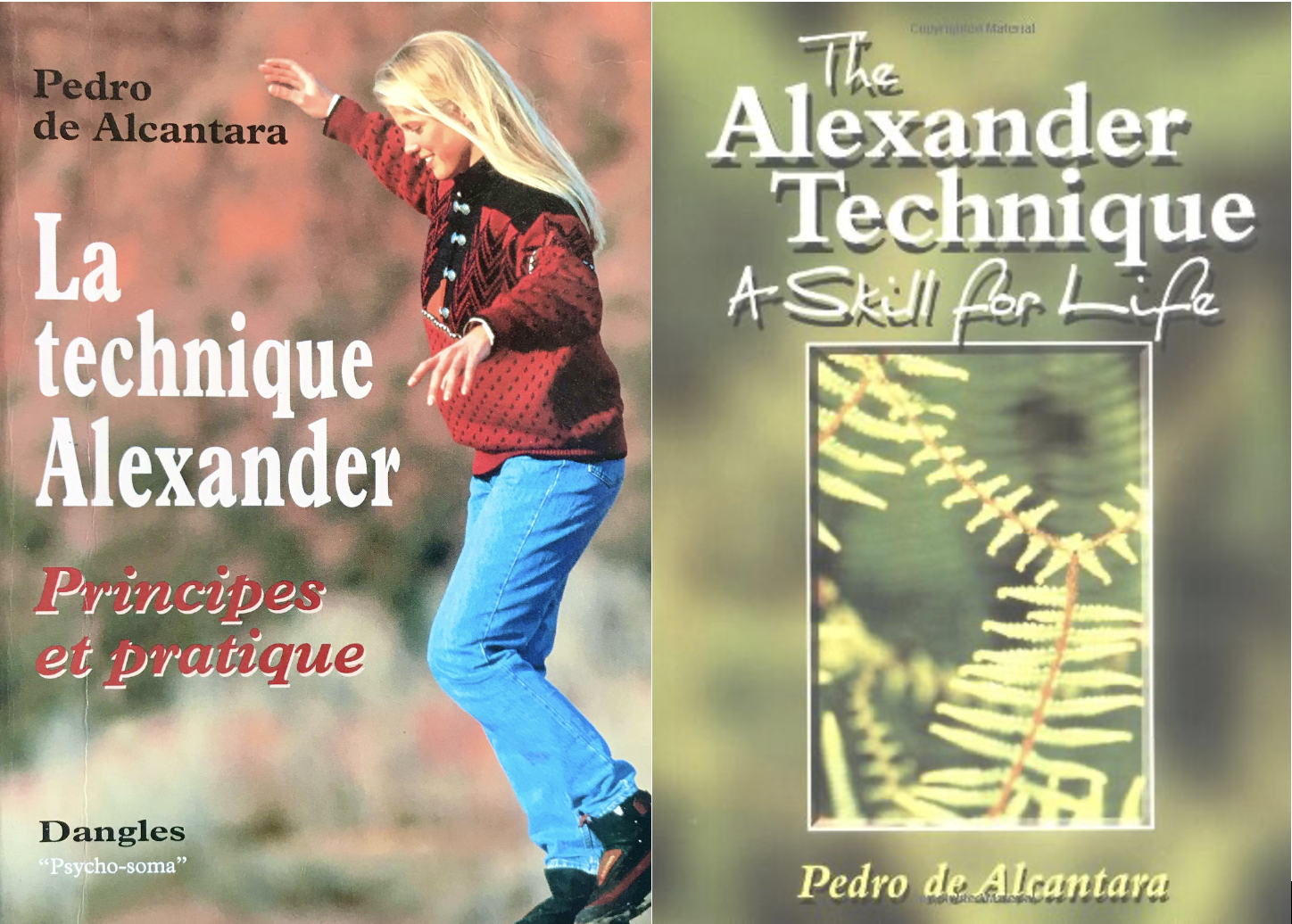

What did I have to lose, other than sleep, my reputation, and the good will of the Gallic nation? I put a book together, writing it in quasi-French. A polyglot student of mine generously helped me translate it into quasi-actual-French, and the resulting book, La Technique Alexander: Principes et Pratiques, was published in 1997 and has stayed in print ever since, liberté, égalité, fraternité.

I then set to rewrite the book in English. Not simply translate it from the quasi-almost-give-or-take-a-fromage-or-three French, but re-think it, write it differently, change my mind about it. The resulting book, The Alexander Technique: A Skill for Life, was published by Crowood Press in 1999, and it also stayed in print continuously until just about now.

Two very different books, representing two very different attitudes. Thanks to the Warm-Hearted Doorman Above (“le mec qui habite au Pôle Nord, quoi”), I had grown a little while grappling with the French book, and I managed to write a somewhat better book in English (quasi).

Some years later, a Japanese colleague who appreciated my writing wanted to translate A Skill for Life into Japanese. “Wait a minute!” I decided to re-read Skill and revise it before the colleague translated it. Ay ay ay ouch! I had changed my mind a fair amount over time, and I now found Skill awkward, to use a euphemism, or awk-awk-awk, to use an onomatopoeia. Let’s not use an expletive. I revised it, my colleague translated it, and the book came out in 2011 thanks to the handiwork of Hitomi Ono, Fumiko Katagiri, and Yoshi Kazami. Soon after, colleagues from Estonia also wanted to translate it, and so they did, using the newly revised text. Alexanderi Tehnika: Oskus Kogu Eluks came out in 2012. I owe this pleasure to Conrad Brown, Karen Brown, and Kristel Kaljund.

Estonian is a non-Indo-European language. It doesn’t share much (or anything at all) with French, English, Portuguese, German, or—well, it shares a little with Finnish. To make a long story short, when I read my own book in Estonian I don’t understand a word of it, analphabète diplômé, Bachi-bouzouk de tonnerre de Brest!

About 18 months ago, my friendly friends at Crowood Press reached out to me and said, “Wait a minute!” They said, “Hey Pedro wanna rewrite A Skill for Life? Because, Pedro, this book of yours is more than 20 years old, and, Pedro, perhaps you have changed a little over the decades? Or so we hope? To be or not to be?”

I was very grateful for their initiative and support. I rewrote the thing. I kept some stuff and burned the rest in a symbolic pyre. The new book is now out. It’s titled The Alexander Technique: A Skill for Life, completely rewritten and revised and the fellow changed his mind, not that he’s become perfect by any means. Far from it. 144 pages, 50 illustrations.

This book and any other book probably should exist in an oral version only, where every day the writer, having learned and grown, tells it differently, tells it more wisely and more entertainingly, tells it with a little uncertainty and a little distance: “Today it’s like this. Tomorrow, who knows! Qui sait, bougre d'extrait de cornichon!” (This last expression is Estonian for “bougre de zouave d'anthropopithèque.”)

In the absence of the metamorphic oral version, you might be interested in ordering the print version, or the Kindle version which you can download IMMEDIATELY. But hurry! I’m at the risk of changing my mind and writing some other book!!

©2021, Pedro de Alcantara