Have you visited a supermarket on the day and time when the workers are restocking the shelves? Have you walked by a construction site and inhaled the deep cold smell of freshly poured concrete? Have you entered a building through the service door in the parking garage, and have you gotten lost in a maze of corridors trying to get to an urgent appointment inside the building?

I consider all these experiences to be similar. They give you a connection with the backstage, that is, with the workings of a place, organization, or city. When you attend a play, you see it all “up front” as you sit in the audience and watch the action happening on stage. But behind the scenery there are machines, tools, stage hands, procedures, practices, schedules, accidents, repairs, and a thousand other things happening out of sight and most often out of hearing.

Backstage allows the front stage to happen. Workers stocking shelves allow the supermarket to function and to provide you with the goods and services that you need. Whole cities have their backstage of subterranean passages, power stations, sewage lines, tunnels, and cables, allowing you to live safely and comfortably.

I went to Milan recently, to teach two seminars at a guitar festival. I extended my visit by a couple of days so that I could spend some time exploring the magnificent city. One of my extra days fell on a Monday. All the museums were closed. Tourist sites were as if abandoned. I went here and there in the city center, often finding myself completely alone in a beautiful winding street with buildings from three centuries ago. On that lonely Monday, the buildings sweetly whispered their secret stories into my ears. I felt that I was backstage in Milan, exploring the city’s this-is-how-it-works rather than its spectacle. I can’t tell you how happy I was.

In the big cities that I love to visit there are alleyways between buildings with service entrances, garbage disposal, the feeling of mystery and secret, also of danger. This is the backstage of apartment houses, offices, restaurants, shops of all sorts. At night, the backstage is gloriously cinematic. The imagination flies . . . love trysts, drug deals, murders. And rats, although these are much too real. Let’s say that “night is the backstage of day.”

I visit my local farmer’s market twice a week. I like going early in the morning, around 8 AM. In winter it’s dark, and depending on my timing I get to watch the changing light as the sun slowly rises. Some of the stands haven’t finished setting up when I arrive. I see the men and women drag crates from their vans parked at the curb. I see their putting up strings of lights on the awnings above their stands. Boxes of ice with fresh fish, the fish not yet arrayed prettily on the stands. I’m often a stand’s first customer of the day. Twice a week I’m backstage, witnessing my friends’ work, marveling at their skill and discipline, grateful for their dedication and reliability.

Backstage is richly populated. Museum guards, baristas, gardeners, delivery men and women, technicians, receptionists, school crossing guards, cleaners. I’ve had some wonderful chats in São Paulo, Paris, Glasgow, and points in between. The museum guard at the Musée Guimet of Asian Arts whose face hinted at the Buddha, the waiter on a cigarette break outside a restaurant, the cheerful crossing guard who kept something of the child within him, the gardener at the Place des Vosges with the poise and balance of a Tai Chi master. Sometimes the backstage hand is a displaced immigrant struggling between hope and fear, and his smile is heartbreaking to see.

At parties, conferences, meetings, baptisms and weddings I tend to become antsy. Sooner or later I feel compelled to get out of the main venue and explore the surroundings by myself. And I often witness the most marvelous happenings and encounters, in which the interplay between intimacy and formality is different from what we see “in public.”

A piano has a backstage, as does a cello, a guitar, any piece of furniture. “Backstage machinery has backstage machinery.”

We don’t have to stretch the metaphor too far before we understand that each of us has his or her own backstage, the workshop of the mind, the lifts and ramps for delivery, our innermost cleaning closet.

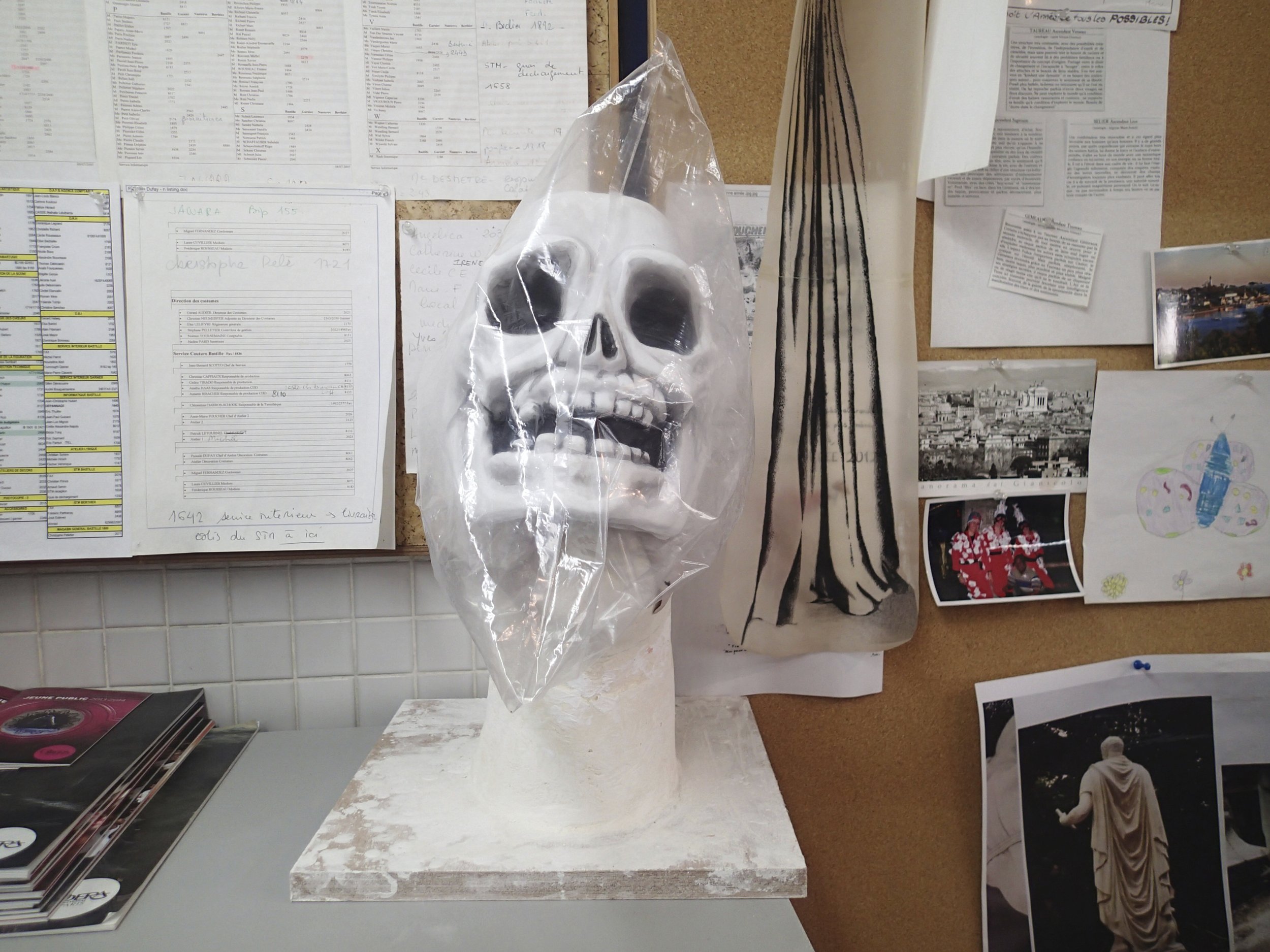

And an actual stage has an actual backstage, believe it or not. Several years ago, my wife Alexis and I were treated to a private tour of the backstage area of the Paris Opera at Bastille. Clothes making, wig making, shoes of all types and sizes; everything crazy and incredible, which is what opera is about. Huge spaces like hangars, industrial machinery, if you’re afraid of heights stay home.

My work as a teacher and coach often takes place backstage. In 2019 I taught an in-depth seminar for the actors of the Comedia Nacional, the main theater in Uruguay’s capital Montevideo. Deep inside, hidden from passersby or prying eyes, we the pros worked together for three days, playing games and learning from one another. During that visit I actually “went to the theater” and watched my colleagues delight the public with their storytelling. And for me to have been part of their preparation backstage . . . wow. Unbelievable.

There’s something exciting and terrifying about the corridors behind the stage, the stairs, the dust, the muffled sounds of your own steps. Because sooner or later you’ll have to pass from the back to the front, and you’ll find yourself naked on stage, in front of an audience. Then you’ll know whether or not you did your backstage job of cleaning up, structuring, and fashioning your music for the benefit of the men and women who came to see you perform.

©2022, Pedro de Alcantara